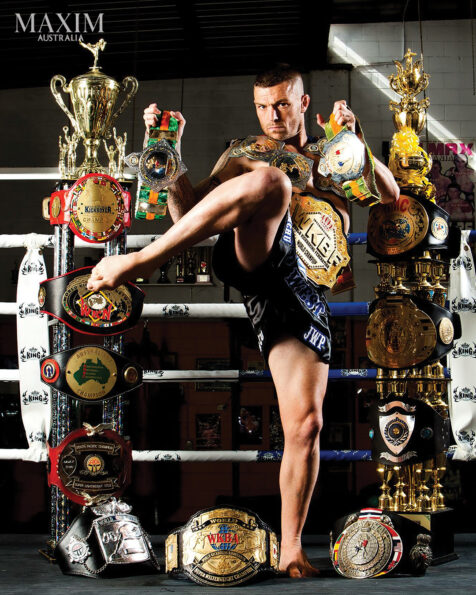

New book The Fighter tells the compelling life story of Australian Muay Thai legend and 10-time world champion ‘John’ Wayne Parr. This excerpt captures his raw grit as he steps into the ring on foreign soil, confronting his fears and showcasing his superior skills. Under the spotlight of Thailand’s epic King’s Birthday fights – the nation’s most prestigious event – he fights to solidify his legacy on the big stage in front of thousands…

The traffic on the way to Sanam Luang park was gridlocked. It was the fifth of December – the King of Thailand’s birthday. To celebrate, every year the King drives through Bangkok and thousands of people line the streets in the hope of catching a glimpse of him as he goes by. Festivities are held in his honour. The crowd light yellow candles that symbolise the colour of the royal family and sing “Happy Birthday”, followed by the Thai national anthem. The most prestigious Muay Thai tournament of the year is held as part of the celebration.

In the end, we had to park a half-hour walk away because the area was crawling with cars. The park itself was shoulder-to-shoulder full of people – it wasn’t until afterward that I was told the crowd in attendance was over 100,000. We worked our way through to the dressing rooms, which were housed in a big marquee. The only thing stopping people from coming inside was a flimsy piece of rope. They stood 10 people deep to watch us prepare in the half-light of dusk on a 38-degree night. It felt more like 50 degrees, with the crush of bodies and the intense humidity.

After a massage, I warmed up by shadowboxing in the dirt. I had to keep my shoes on. I remember all the fighters shadowboxing, almost tiptoeing, so as not to stir up the dust. From the marquee, there was a two-metre-high catwalk that passed above the mass of the crowd to the ring, which was elevated to give people a clear view of the fights. All I could see as I mounted the catwalk was an ocean of heads.

The first time I fought on the King’s Birthday, my knees went weak, and I spent all my pennies in the first and second rounds. This time, I told myself, I’m not going to let the crowd intimidate me. This time, I’m not going to be afraid. I’m going to absorb each and every one of them. My cornermen held the top rope down so I could step over, giving the appearance of confidence, regardless of how I actually felt. Once I had entered the ring, I began my Ram Muay.

Ram Muay is short for ‘wai khru ram muay’, which, roughly translated, means ‘war dance saluting the teacher’. In performing it, the fighter pays respect to all who have come before, defining Muay Thai as an art form going all the way back to Buddha, Dharma and the god Hanuman. From there, the boxer invokes all of the teachers, ancestors, trainers, family and friends who have contributed to their presence on that day. Practically speaking, the dance consecrates the ring and the contest that follows as something more than just a competition: it becomes the performance of a ritual.

As I went down for the first prayer, I asked Earth, Wind, Fire and Water to give me strength. Then, for the second verse, I invoked my mum, dad, grandparents, people who were deceased: all my ancestors. For the third verse, I invoked my pad holder and sparring partners. I added an extra verse, seeking the blessing of my friend P-Tung, who had just passed. I asked the gods for strength, courage and power.

Every element of my career was focused on that precious moment. I used the Ram Muay to call on every aspect of my life and preparation, past and present, drawing all of it toward me. Planglit, my opponent, had finished as much as a minute earlier. He stood waiting, politely, gloves by his sides, focused on his thoughts. He had established himself as a rising star – and was looking to step over me and onto the top tier of the competition. I knew, however, that I was the best I’d ever been.

I danced from rope to rope, stretching out my body, looking into the crowd. The ref brought us together to inform us of the rules. It’s always the same thing, so I wasn’t really listening; I was trying not to look away. I wanted to stare Planglit down. For the first time, I had a proper gauge of how tall he was; I’m five foot ten – he was two inches shorter. He wouldn’t look me in the eye. When I went back to my corner, the ambassador of the Australian Embassy, William Fisher, took off my mongkon. Wearing a shirt and tie, he was perspiring less than I was. With a slap on the shoulder, he said, “Go do this for Australia.”

What I had been taught by Paul Briggs, my training partner back in Australia and a world champion in his own right, settled over me. He coached me to believe in myself. That belief was in his mindset; it was how he took on fights. You don’t fight in fear of the opponent. You fight because you love it. It’s not referred to as the ‘art’ of Muay Thai for nothing. It’s the rawest form of sport there is. From the dawn of time, men have been fighting, giving it one expression or another, each with its own formalities and rules. I’d had around 70 fights trying to escape its pull.

As I was entering the ring to face Planglit, Muay Thai had become a vocation. Every single fight brings me closer to realising my dream. I don’t fight for money or fame. I’m fighting for legacy. I’ve become addicted to the rush, to the crowd, to the applause. If you conquer your demons in the ring, if you can conquer them in sport, you can do anything. That said, by now I don’t really have any demons. All I do is fight. I don’t drink, don’t do drugs. I just eat, sleep, run, train and fight. There are no distractions, no outside influences.

I wanted to put on a masterclass for everyone there watching that night and was excited to fight in front of the King on his birthday. The bell rang. From the moment we touched gloves, I felt as though I couldn’t put a foot wrong. I felt as if I was two steps ahead of Planglit the whole time, scoring, blocking, countering. The fight passed as effortlessly, as naturally as a dream. I ran around the ring after the final bell with my hand raised, acknowledging the crowd.

Each individual moved as part of something much bigger, like waves on the surface of the sea. The referee gathered the scorecards and, once he’d reached the third judge, raised his hand toward my corner, indicating I’d won. William Fisher and my trainer, Sangtiennoi, burst through the ropes. I looked around to see where the television commentator was. I leaned through the ropes and said – in Thai – “Give me the microphone.” He refused. So, I demanded it. “Just give it to me.” Reluctantly, he handed it over. I returned to centre-ring to address the 100,000 people there in the park, as well as the 20 million watching at home, including the King himself.

Again, in Thai, I said, “Thank you for cheering me on during tonight’s fight. I hope you were all entertained. Long live the King!” The crowd erupted as I handed the microphone back. As I returned to the marquee, complete strangers came up to me, cheering and shaking my hands and touching any part of me they could reach. One of my cornermen later told me that Planglit had been berated by his trainer: “You’re a disgrace! You’re pathetic. How could you lose to a farang?”

I’d broken his nose somewhere near the start of the fight and then broken his left arm while kicking his body. He showed no signs of pain. For five rounds, he just kept walking forward. On that night, 10 farang (Westerners) had been selected to fight the 10 best fighters Thailand had to offer and I was the only one to win.

THE FIRST KING’S BIRTHDAY FIGHT

Mr Songchai, promoter extraordinaire, came through in the end, offering me a fight on the King’s Birthday card. Short of a major stadium title fight, the King’s Birthday is the most prestigious occasion on the Muay Thai calendar. Sangtien, my trainer, was fighting as the main event against Moroccan superstar Hassan Kassrioui. Kassrioui was a taekwondo stylist with the complete set of jumping, spinning kicks; the full tornado of crazy. Because nothing like that had been seen before in Thailand, he was known as Mun Mar Juk Narlok: ‘He Comes from Hell’.

The day before, Sangtien and I did the usual sweatsuit run and, having both made weight, sat down to relax. The stereo was on, the kids were playing and Sangtien was in the kitchen, cooking for everyone who was able to enjoy it. I sat downwind so I didn’t have to think about food. The sound of breaking glass cut through the night. Por, my trainer by contract, was back. “You think you’re all so clever, don’t you?” he screamed, waving his crutch as he came in the front gate. “How dare you make John Wayne fight at the festival and not give me my share of the prize money?”

Por continued to smash things while the rest of us ran out into the street. How do you fight a one-legged, elderly man on a crutch? We went and hid in a nearby alleyway. An hour later, we asked one of the local kids to ride past the camp on his pushbike. When he returned, he said that the coast was clear. Por had got into a cab and left. “You’re fighting tomorrow, John Wayne,” said Sangtien, “so you need to get some rest. You go back to the camp to sleep; the rest of us are going to go to a hotel. Someone will collect you tomorrow and drive you to Lumpinee to weigh in.”

What the hell? I thought. Why do I have to go back to the camp by myself? I quietly entered through the gate and, fortunately, the place was deserted. I went to the boxers’ room, praying that Por wouldn’t come back. I tried to get four hours of sleep before I’d have to wake up to leave. I slept with one eye open and, when the alarm went off, I got up feeling like I had a hangover. The weigh-in at Lumpinee was what I’d come to expect, and we then went straight to a hotel to relax for the day.

Come three o’clock, my trainer Sangtien, pad holder Barnork, training partner P-Nop and myself climbed into the minivan and set out for the venue, Sanam Luang park. My teammates had underprepared me for the scale of the King’s Birthday celebrations. King Bhumibol Adulyadej was beloved by his people and they had turned out en masse to pay tribute. We had to leave the car and walk 20 minutes to reach the park. The main street was choked with a bustling crowd. The afternoon was turning to dusk as the long, tall figures of the Wat Phra Kaew temples reached up into the sky.

A concert was in full swing on one side of the park and the sound of the modern music flowed down to where it blended with the traditional Thai dancing on a nearby stage. The ring itself was set up in the middle of the grounds. Warm-up and rubdown was a hurried affair in a makeshift tent that contained all the boxers fighting on the show. We pretty much ignored each other, separated into our own worlds by the dust and the shadows. The temperature under the tattered sheet of canvas must have been 50 degrees, with the boxers’ fumes bouncing back at them from the wall of onlookers who stood just beyond the awning. When my name was called, a police escort forged a path through the crush.

Once I had climbed the ropes, I looked out across the immensity of the people. The ring was like a tiny boat held aloft on an immense body of water. My knees gave way, and I had to clench my guts to stiffen them again. I began my Ram Muay but I felt the pressure of the crowd and the sky, two sheets that pressed together, emphasising how small and alone I really was. After the bell went, I resorted to what I knew and applied as much pressure as I was able. My opponent fought smart by shutting me down in the clinch and sapping my energy. When the bell went and I sat on my stool, instead of being given instructions, I was threatened. “If you don’t win this fight, we’re going to bash you when we get back to camp.” It was a close fight over the next three rounds – the only fight I’ve had that was fought almost entirely in the clinch. With every round break, my corner became increasingly frustrated.

By the final round, I had spent all my pennies and my opponent dumped me on the canvas. Thirty seconds after that, he dumped me again and the fight was no longer close. When the bell rang to close the final round, I knew that I had lost by decision. No-one spoke to me in the change room; all I received were dirty looks. We stopped off for food on the way home and I sat isolated at one end of the table. I was dreading what the Thais refer to as ‘round six’, which means being beaten up once you get home.

Suddenly, P-Nop snapped out of his filthy mood. He patted me on the back and said, “It was a hard fight. You did your best.” We returned to the camp exhausted from the fights, the crowd, the heat and dust. Por was waiting for us. “This is my camp, my home!” he screamed as he waved his crutch in the air. “If you don’t like the way I do things, you can be the ones to move out!”

Sangtien found a unit down the street with four bedrooms, close to the other gym we were training at. He asked me what I thought. I didn’t know what to say. My 12 months were up. I was ready to get on a plane and return to Australia, leaving the whole mess behind me.

THE THIRD KING’S BIRTHDAY FIGHT

I got an email from Mr Songchai shortly after, asking if I’d like to appear at the next King’s Birthday celebrations in six weeks’ time. The offer was to fight Duen Easarn. Duen was a young, strong, orthodox fighter from Bangkok. He was probably ranked in the top five in his weight division. I accepted, rang Sangtien and made arrangements to stay with him three weeks out.

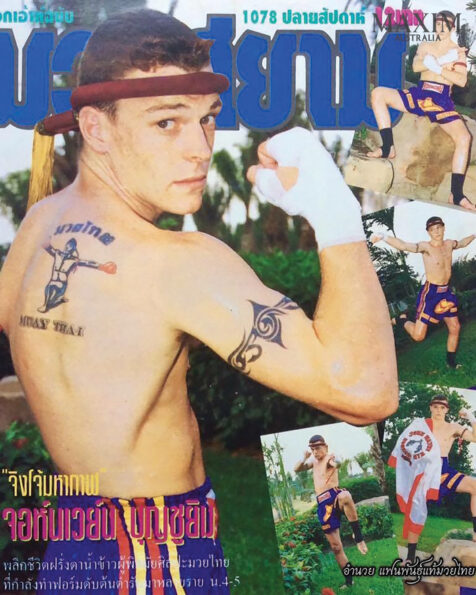

The weigh-in was like a scene out of the Wild West. As soon as I walked through the door, the room fell silent and all eyes turned toward me. It was the first time in my career that I felt like I was somebody. I didn’t even make the local paper in my home country but in Thailand I was ‘The Dangerous Kangaroo’. Duen and I got on the scales; I came in two kilograms heavier.

Mr Songchai said, “We can’t sanction this fight. You’re too big.” He snapped his fingers. “I have the perfect solution. Masato was supposed to fight Orono but pulled out because he believes Orono has hepatitis. How would you like to fight him instead? It will be for the IMF world title.” This was the definition of esteemed company. Orono, veteran of over 300 fights and slayer of the great Ramon Dekkers, had stopped me by way of an elbow that felt like a baseball bat when it landed. Masato, on the other hand, was analytical and surgical; the metrosexual king of the K1 Max.

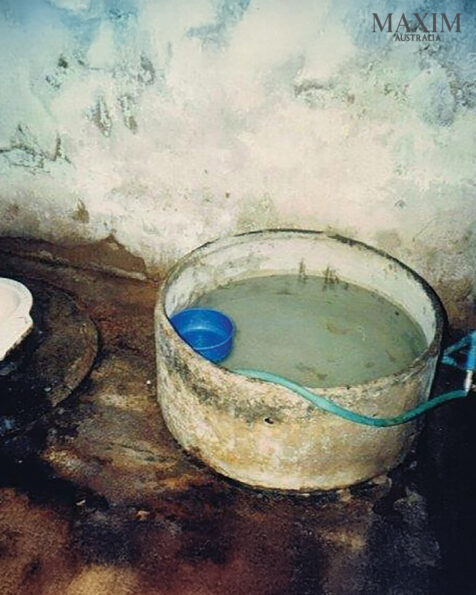

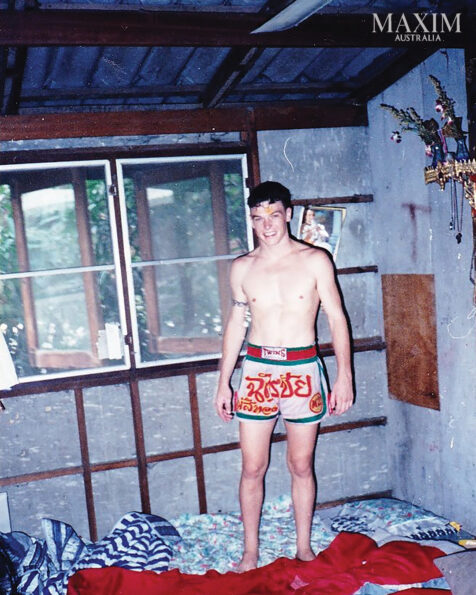

I wouldn’t have cared if Orono had rabies and Mr Songchai changed the rules to include biting in the clinch. A world title in Thailand was the Holy Grail. I accepted and immediately ran to the nearest payphone to ring Sangtien. “We have a major problem,” I said, panic rising in my throat. “Mr Songchai asked me to fight Orono – and I accepted.” “Relax,” he said. “I’ve got a game plan. I’ll let you in on it tomorrow.” “Can’t you tell me now?” “If I tell you now, you’re just going to panic and it’ll do you no good.” “I’m panicking anyway,” I replied, before I realised he’d hung up. I was back to sleeping in a cupboard but at least I had a double bed mattress on the floor. This camp was even worse than the last one. The shower was another splash-on/splash-off affair with cold water in a basin.

Even worse luck: the camp was out in the countryside. If you wanted to go to the shops, it was a 20-minute trip by motorbike. There was no internet, so I had to amuse myself by reading books and listening to my Walkman. After a sleepless night of nervous vomiting and diarrhea, it was time to get out of bed and face the music. “What’s the game plan?” I asked Sangtien the second I saw him. “Easy,” he replied. “We’re going to go southpaw against southpaw.” I looked at him in disbelief. “I’m going to get in and fight a guy – a monster – who’s had 300 fights in his own stance, even though I’ve never trained southpaw in my life?” “Think about it,” said Sangtien with the relaxed tone of a man who was not fighting Orono later in the day. “What did he really hurt you with last time? His left elbow. His left elbow is his strongest technique. If you stand orthodox, it’ll come straight through your guard and land flush on your face. If you stand south,” he said, shifting his own stance and rolling his shoulders in rhythm as he lifted his hands to guard, “your right arm will block the trajectory of his. There’s also something suspicious about his lead leg. Every time he kicks, you check and kick straight back while his weight is on that lead leg. Come on, I’ll show you.” He picked up a focus mitt off the apron as he climbed into the ring.

Half an hour of discussion and drilling technique in the ring didn’t calm my nerves in the slightest. In fact, it made me even more anxious. As I climbed the stairs to my cupboard to lie down and relax, a memory of Orono’s face during our last fight appeared in my mind. I had hit him with a solid left and right. Both punches snapped his head back on his neck and, when he looked at me, he growled like a Doberman and banged his gloves together. I heard a voice in my head telling me there was no way I could do it. I kept that to myself, however; I didn’t want Sangtien to think I was a pussy.

The King’s Birthday was the same set-up as the year before, except it was even more pressure this time because I was one of the main events. As I was waiting at the foot of the catwalk for the previous fight to finish, my inner demons were arguing with each other as hard as they could. I can’t do this, I thought. I can’t do this. I finally came to the conclusion that I’d stand south for a round – if it didn’t work, I’d go back to orthodox. As I walked over the heads of the crowd, I kept my eyes on the catwalk in front of me. The whole thing felt like the carriage climbing upward on a rollercoaster.

After performing my Ram Muay, I stood eye to eye with Orono while the referee gave his instructions. Orono was staunch. He looked at me like he wanted to drink my blood. I tried to give him the impression that I was more experienced than I really was, and not prepared to give an inch. As soon as I came out of the corner in a southpaw stance, he was visibly thrown off. Every time he’d move in to attack, I’d counter with a push kick or a leg kick. As the fight wore on, my confidence grew, and I was able to land almost every combination I threw. Once Sangtien’s plan began to work, I felt completely comfortable.

Orono was what is known in Thailand as a ‘crowd fighter’. He’s a national treasure – when he fought, it was seen by the crowd as Thailand versus the world. Mr Songchai knew that if he put Orono on a show, attendance would be at capacity. Every time he threw a combination, the crowd would cheer. Once I started to excel, they went eerily silent. At the beginning of the fourth, he landed the deadly left elbow, opening up a small cut under my left eyebrow. Blood began to run into my eye, obscuring my vision. I became desperate, fearing the fight would be stopped just when I’d managed to get control of it. I went up a gear and threw everything I had. Just before the final bell, I dumped him from the clinch.

As soon as the bell rang, I ran around the ring with my glove in the air, saluting the crowd. I dropped to my knees at Orono’s feet to honour him. He shrugged and walked away just as the world title belt was being cinched around my waist. Again, I dropped to my knees, this time at Sangtien’s feet, honouring him for making my dream come true.

We returned to the change room and Sangtien said, “Give your belt a kiss. It’s time to say goodbye.” I looked at him in disbelief. “No-one’s taking this off me.” “This is Thailand. If you want the belt, you’ve got to buy it. Now give it a kiss and hand it to the man. We’ll order you one with your name on it tomorrow.”

Sangtien went and collected the prize money the next day. It was my biggest purse ever: 70,000 baht, the equivalent of 3,500 Australian dollars. I attempted to give half to Sangtien but he refused. “You’re not my fighter – you’re Por’s fighter,” he said. “You learned everything from him. I hardly have to teach you anything. All you do with me is get fit.” The IMF world title was my second world title win in two months. When I returned to Australia, the silence from the media and public at large was deafening. I needed to find some way to make an impact in my home country.

THE FOURTH & FINAL KING’S BIRTHDAY FIGHT

Sangtien welcomed me with open arms. I was scheduled to fight up-and-comer Duen Easarn, my original opponent from the year before. I had also organised a fight for Rex Redden, a training partner and friend of mine from Australia who had travelled with me. Rex was a tough, experienced Thai boxer from New Zealand. He had moved to the Gold Coast and dropped in one day to check out the gym and soon became part of the family. I felt he was up to the challenge, so I put him forward as a prospect for Mr Songchai. It was going to be fun to train together and then corner one another when the fights arrived.

It was half an hour by taxi from the airport to Sangtien’s new camp. This time, he’d set up near the markets. There was also a hospital nearby, which could come in handy. All the old fighters and pad holders were still there, and I felt like I was home. Mr Songchai had matched Rex against former Lumpinee champion, Koaponglek. “Who’s that?” asked Rex. “Some Thai,” I said.

I was now in fear for Rex’s life. Koaponglek was a designated killer with something like three hundred fights. He threw elbows like a sprinkler waters a lawn. He would regularly destroy his opponents, not just beat them. If he knew he was fighting a Westerner, he wouldn’t be losing any sleep. By this time, Sangtien had begun to breed fighting roosters. During the day, they went out onto the lawn in their cages; at night, the cages were pulled under cover, onto the carpet area where the bags hung. The following morning, there would be a sea of shit in the training area.

Because Rex wasn’t used to the conditions, he developed blisters on his feet, which soon became infected. He could barely walk because the pain was so bad. He had to go up to the hospital and was diagnosed with an infection that required strong antibiotics. He was forced to withdraw from his fight. I’m not sure if it was the chickens but I came down with bad gastroenteritis. I was shitting and vomiting constantly. By midnight, I could no longer stand the pain. I dragged myself up to the hospital, where I was put on an IV to be rehydrated. Once I stopped vomiting, I was released and staggered back to camp.

At four in the afternoon, the boys went out to run but I stayed in the cupboard. Later on, I could hear them hit the bags, then clinch. Just as they finished, Sangtien screamed out my name. “Why aren’t you training?” “I’ve got gastro.” “So?” “I thought I’d give it a day to try and recover.” “We don’t have time,” he said. “Put your shoes on and run a few laps of the block.”

I made weight at 72-and-a-half kilos the next day and, again, Mr Songchai threw the curveball. “We’re planning to do an eight- man tournament for the first time, instead of single fights. Now you and Duen are both admitted to the super eight.”

The next night saw another 100,000-strong crowd in Sanam Luang park. After my Ram Muay, one of the officials climbed into the ring with a blazer. I was called to centre-ring and the blazer was draped over my shoulders. Known as a ‘sua samart’, the blazer is an award for services to Thailand and Thai culture. It is a rare honour. Sangtien took the blazer and left the ring. Now the pressure was on me to perform. The fights were three three-minute rounds with a minute’s break, instead of the traditional Thai structure of five rounds of three minutes with a two-minute break in between.

The usual Thai structure makes for a slower-paced contest initially, in which both fighters can feel each other out. The tournament structure makes the fight much more like a race: you have to get out there and make your mark as quickly as you can. By the end of the second round, I was just behind on points. Sangtien told me to pick up the pace and I obliged, getting busy with my recently developed boxing skills. Once I’d hurt Duen, I kept up the intensity. By the final bell, I had done just enough to win the fight. I was happy with my performance and physically I felt fine. I got an ice massage back in the tent and lay with my legs up until 15 minutes before the next fight, when I had a Thai oil massage to pick my body up again.

My next opponent was a Portuguese fighter, Miguel Marques. I wasn’t fazed. Having been in Thailand so long, I wasn’t going to be intimidated by another Westerner. I felt that Miguel’s comparative inexperience gave me the opportunity to play to the crowd and work at a slower pace. By the end of the third round, I’d seized the decision. My old foe Nuengtrakan met me in the ring later in the evening and we were both surprised to discover that there was to be no final. The announcer explained to us and the crowd that we would both be representing Thailand in France in another eight-man tournament, to be held in three months’ time.

The crowd was disappointed but I was relieved – Nuengtrakan was a monster and had beaten me twice. I didn’t want to face him until I was fresh and fully recovered. The Australian media might have remained silent but I was the talk of the internet. I had won three times in three successive King’s Birthday events and was the only Western fighter ever to do so. Representing Thailand in France meant that the world saw me as Thai. The blazer I had been awarded was the crowning glory of that achievement.

This is an edited extract from THE FIGHTER: THE LEGENDARY LIFE OF AN AUSTRALIAN CHAMPION by ‘John’ Wayne Parr, with Jarrod Boyle (Hachette Australia, $34.99) available in all good bookstores

By ‘JOHN’ WAYNE PARR WITH JARROD BOYLE

For the full article grab the January 2025 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.