New book The Immortals of Australian Football celebrates a collection of legendary players from the AFL and its predecessor, the VFL. This month, we look at the life of arguably the most famous personality in the history of the game – the iconic RON BARASSI…

In most of the things that Ron Barassi did, he was an innovator and leader. He is one of the biggest names the sport has ever seen, and the number 31 on his back is one of the most famous numbers in all of Australian football. But his legend started with his father’s death in World War II, a death that inspired his young son to climb to the top. Ronald James Barassi was a handsome man from Castlemaine who debuted for Melbourne when his first and only son was a little less than four months of age. His final game was a victorious Grand Final in 1940.

BRILLIANT BARASSI

| Name | Ronald Dale Barassi |

| Born | February 27, 1936, in Castlemaine, Victoria |

| Died | September16, 2023 (87 years) |

| Nicknames | Barass, Mr Football |

| Height/weight | 179 cm, 87 kg |

| Clubs | Melbourne, Carlton (VFL); Port Melbourne (VFA) |

| Years active in VFL | 1953–1969. Debut: 17y 78d; last: 33y 79d |

| Positions | Midfielder/ruck-rover |

| VFL/AFL player # | 6329 |

A little over 10 months later, he was the 10th VFL player killed in World War II. Ronald Dale Barassi – it was Ronald Dale rather than ‘Junior’ – was five years old at the time and, as you would expect, this framed his future and guided a dream. Number 31 was the jumper his father wore. It was his number for 253 of his 254 games, only switching to number 2 for the 1958 Grand Final after the teams were forced to play in different numbers because The Sun News-Pictorial had illegally published the jumper numbers and to protect the sales of the Football Record, the VFL made everyone change but Ray Gabelich (there was no other jumper big enough for him).

Under each autograph he signed, he finished with 17410–31. Our sport, like most, is measured by numbers; in this case, it is ‘17’ Grand Finals, ‘4’ clubs and ‘10’ premierships as player and coach, and that number ‘31’ he made famous on his back. Barassi was a pioneer in many ways. He was a life member of four different clubs (which is the most on record for any one person). The father-son rule was created for him. The ruck-rover position was ‘created’ for him by Norm Smith.

His move from Melbourne to Carlton for the start of the 1965 season was regarded as the ‘death of loyalty’ and a game-changer in terms of player mobility. It broke the hearts of Melbourne fans. Melbourne won the 1964 Grand Final and then went on a period of instability and would not win another Premiership until 2020. Then, as a coach, he used player moveability to build North Melbourne into a Premiership-winning team after a multi-decade record of losing.

The Barassi family had been living in and around Castlemaine since they arrived from Italy in the mid-1800s, but ‘big’ Ron moved his family to Footscray so he could play football for Melbourne, which is where Barassi and his mother were living in 1941. In Ronald Dale’s case, the family farm was in Guildford, and that is where he returned without his mother after the death of his father, embraced by the extended family, which is so often the case for those of Italian descent. Young Barassi’s story is not unique from that time, with 34,000 Australians losing their lives in the war, but it was significant, and shaped his life.

He grew up with not many kids of his age nearby. His football was framed by kicking the ball to himself. At primary school, he quickly became the lead athlete. He tested himself by goals, not by those around him. Aged 11, Barassi moved back to live with his mother, and over the next couple of years the rest of the Barassi clan left the region, either through death or marriage. His mother had remarried and moved to Box Hill with her new husband, but that didn’t last as Ron and his mother fled domestic violence to live in a bungalow at the back of a home in Williamstown, before eventually settling in Brunswick.

He was taught to be a hard man, never stepping back from a fight or a struggle. It evolved into the determined and focused look that typifies many of his playing photographs. Or the legendary coaching ‘explosions’ that are oft replayed today. His mother eventually married for a third time and moved to Tasmania, but Ron stayed in Melbourne with one of his father’s teammates, now Melbourne coach, Norm Smith. In Smith’s eyes, young Ronnie wasn’t tall enough to ruck but he was too tall to rove. He was fast and strong but didn’t have the discipline to hold down a key position.

In 1953, he was in and out of the side. He played only six senior games for the season and Smith wrestled with what to do with him. He knew he had a special talent at hand, but he couldn’t work out how to use him. He was 17 but built like someone much older. But first he had to jump a hurdle, one placed before him and Robert Pratt, the son of South Melbourne legend Bob Pratt. Melbourne and South Melbourne lobbied the VFL to create a father-son rule that would allow them to take the sons of their heroes rather than have them run the gauntlet of the zoning system and the need for transfers.

For Barassi it accelerated his climb from the Under-19s, often called the Thirds, in 1952 into the Reserves and the Seniors in 1953, even if it didn’t work too well at first. Melbourne wasn’t too good and only won three games for the season and finished second last. But Smith was cooking something and he was recruiting young players he could shape, rather than older players who felt like they were already there. He was building a team and nothing else mattered but the team. Smith, like his brother Len who would coach Fitzroy in 104 games, was an innovator. He was looking for something different, and the boy living in his backyard was just what he was after – when he worked him out. What was seen as a lack of discipline would become his greatest strength. It was actually the stepson of the Red Legs’ second coach that cottoned onto the idea that you just had to let Barassi chase the ball. That is what he wanted to do, that is what he was designed to do.

‘death of loyalty’

He was born with endurance, but he trained that to perfection. So, they unleashed him in the Reserves, and with ruckman Terry Gleeson he started to dominate. After playing round two and three in the Seniors, he played in the Reserves until round 10 when he earned his recall. He never played seconds again. He played as a ‘rucking rover’. He was 179 cm in the new language, which was just a little short to hold down the first ruck slot, but way too big to be a rover. He was told to run around and make a nuisance of himself, which he did free of the shackles of a regular position. All he had to do was chase the ball, and he was good at that.

The round 10 clash against Footscray was only his fifth full game. This was in the days before the interchange. If you started on the bench you wouldn’t come on until late unless there was an injury, and if you were on the ground and benched, that was it for the day. Newspapers started to refer to him as a follower, and a new position in football had been created. As the Barassi experiment started to work, Melbourne lifted and it snuck into the finals, then won its first two finals to make the Grand Final against Footscray, the first of seven Grand Finals in a row.

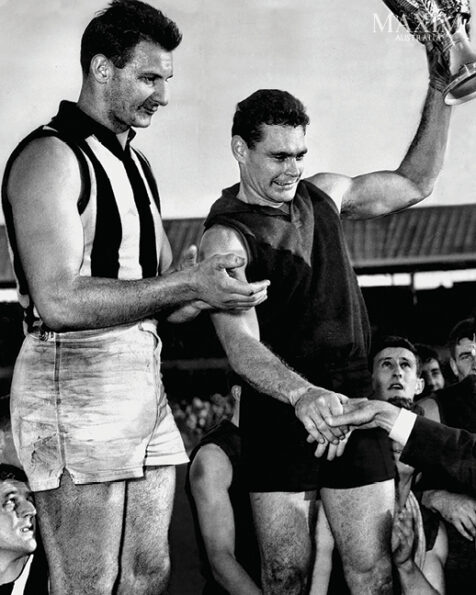

Melbourne was beaten soundly by Footscray, with fellow Immortal Ted Whitten playing a key role. But Melbourne was young, with six teenagers in the side. They lost that day, which was as expected, but then won five premierships in six seasons. With Barassi’s impact on the game growing, Melbourne backed up the 1955 win with premierships in 1956 and 1957, before losing in 1958 to arch nemesis Collingwood, which is the game in which he wore the number 2. They bounced back in 1959 and 1960. By 1960 the 24-year-old Barassi was the captain.

He had one more Premiership with Melbourne in 1964, making him a six-time Premiership player before he was 29. He had won 149 of his 204 games with Melbourne and, even though he had missed only 32 games across his career, his body was showing signs of wear and tear. He had a shoulder injury that meant it could dislocate while sneezing, but according to records of the day he regularly dislocated other joints as well. He was a crash-and-bash footballer. A pack of players around a ball represented a bunch of people between him and the object of his desire. So, he went and got it and to hell with anyone in his way.

Like Jack Dyer a few decades earlier, even though he played a brutal brand of football, he was clean. He was suspended for four games near the end of 1963, which would have put him out of a Grand Final had Melbourne made it. He was angry about the decision and again the rules were changed because of Ron Barassi. He felt the TV footage from GTV9 at the time would have cleared him, but clubs weren’t allowed to use it at the tribunal. After the furore that followed his suspension, the rules were changed to allow video to be used as evidence.

With his body failing him, somehow, he made it through 1964 with enough form to win his second club Best and Fairest and he also held the Premiership cup aloft as captain. But he was thinking ahead now to his future, when Carlton came to him with a captain-coach offer. Even though Norm Smith anointed him as his successor, there was no guarantee when that would happen. In the days leading up to Christmas of 1964, Ron Barassi jumped ship, and the vitriol was palpable. The Melbourne hero was changing clubs, and it was almost as if the 12 years he played Senior football were lost in what was termed the death of loyalty.

Carlton was a disorganised mess when he joined. It was more than just the money, which was impressive for the time, it was about finding a way to keep the competitive flame flickering. He was going from a Premiership team to one that had won only five games and experienced its lowest ladder finish in its history. In the papers, the deal was for £9,000 over three years, which was a considerable step-up from what he could have earned at Melbourne. Carlton President George Harris, who was the architect and salesman of the deal, said many decades later that the pay was actually slightly more. There was also a sign-on bonus and incentives, £500 for making the finals and £1,000 for a flag.

The numbers were small, even in relative terms, by today’s standards. Barassi was a million-dollar footballer in terms of marketability and football ability. This deal was in today’s figures less than $300,000 for three years. In 1965 and 1966 Carlton won 10 games and then the third year of the deal, it made the finals. As a player, his first two seasons were curtailed by injury, and he played only about half the games, but in 1967 he played every game. That was the peak of his playing days with the Blues.

| Key stats | |||

| VFL/AFL debut | Round 4, 1953: Melbourne v Footscray Venue: MCG Date: Sat 16 May 1953, 2.15 pm Attendance: 23,829 | ||

| Playing career | Premiership matches | ||

| Years | Club | Games | |

| 1953–64 | Melbourne (VFL) | 204 | |

| 1965–69 | Carlton (VFL) | 50 | |

| 1972 | Port Melbourne (VFA) | 4 | |

| Total | 258 | ||

| Representative team honours | |||

| Team | Games | ||

| Victoria | 19 | ||

| Combined total | 277 | ||

| Honours | 6 x Premiership Player 3 x All-Australian 2 x Melbourne Club Champion 4 x Premiership Coach | ||

| VFL/AFL jumpers | Melbourne: 31, 2 (one game, 1958); Carlton: 31 | ||

He played his final game in 1969. In 1968 he pinged a hamstring in round five and didn’t return until round 14. But six rounds later, on the eve of the finals, he retired as a player and his coaching went up a notch, although he played one game in 1969. His preparation for coaching was as relentless as his preparation for playing. With the extra time afforded by not training, he concentrated on his players and the opposition.

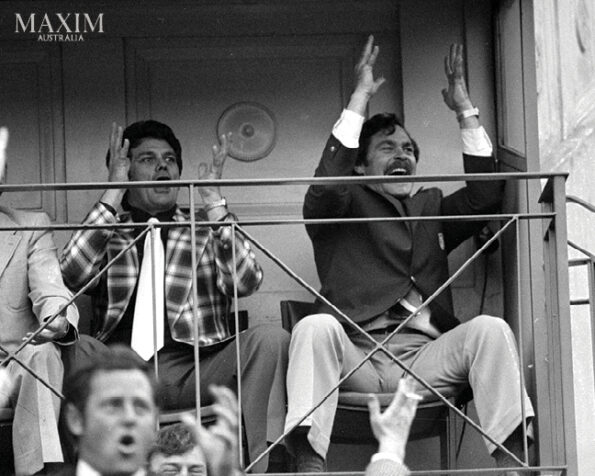

The Navy Blues won the 1968 flag with Barassi sitting in the coaches’ box – although still the captain of the side. They played an exciting brand of football. It was fast and play-on at all costs; a ‘catch us if you can’ brand of football., Essendon couldn’t. Carlton lost the 1969 decider and then won the infamous 1970 Grand Final in front of the largest crowd at the time in Australian sporting history.

In terms of playing, he fronted up for the 1969 season but got only one last game, fittingly against Melbourne. In 1971 he stood out of football to concentrate on business, but was coaxed back into coaching by North Melbourne and took the Kangaroos to two flags – the 1977 victory his 10th and final Premiership. He later coached both Melbourne and Sydney.

There are so many ways that Barassi changed the game and the VFL. The chiselled jaw was often clenched in determination. The eyes were always fixed on where he was heading, and as a coach, he could make the toughest of men quiver in a corner with a spray. Few players have ever been as good, few coaches have ever left such a mark.

By ANDREW CLARKE

ALL PHOTOS: © NEWSPIX

This is an edited extract from The Immortals of Australian Football by Andrew Clarke (Gelding Street Press, $39.99) available at BIG W and all good bookstores