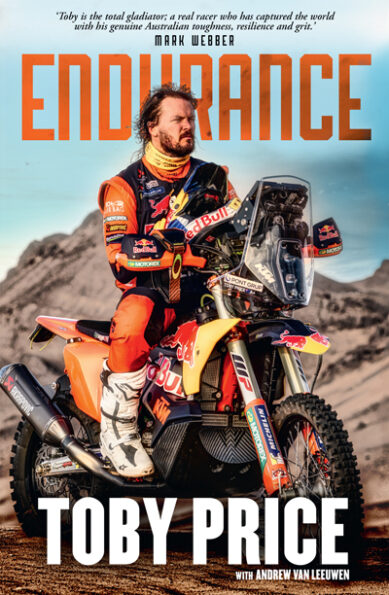

The Australian bush has conjured up some crazy legends and their life stories, but the rise, trials and tribulations of two-time Dakar Rally champion and imminent icon of Aussie motorsports, TOBY PRICE, is surely one of its best…

As a two-time Dakar Rally champion, seven-time Finke Desert Race winner, FIM World Rally Champion and one of Australia’s most popular motorsports athletes Toby Price has lived a truly remarkable life filled with ups and downs. A childhood racing prodigy from the tender age of two, Toby ripped through the junior ranks, taking out titles in both dirt track and motocross, and turning pro at 16 joining the formidable KTM Racing team. Soon he was turning heads internationally and tapped to take on the most forbidding enduro courses the sport could throw at him. Who knew that the remote town of Roto (population: 41), in the far-west of NSW, would be the launching pad of one of the greatest motorsports athletes the world has seen, fit to tackle and triumph over the planet’s most gruelling endurance race? But the clock and the elements weren’t his only adversaries.

Widely renowned for his “Bush Mechanic” persona, Toby has overcome many formidable bumps in the road — the death of his adored sister, Min, the tragic loss of mentors and rivals in the desert, countless broken bones and an accident that should have paralysed him for life. His story is a study in staying true to yourself and following your passion to its ultimate end. The person who emerged from the crucible of so many trials is a kid from the country whose need for speed took him to the top of the podium, recipient of an OAM at age 33 and now one of the most beloved figures in Australian sport.

In his latest book, Endurance: The Toby Price Story, the world champ shares his incredible and inspiring journey and in the following edited extract talks about overcoming immense adversity — from a life-threatening neck injury, being screwed by insurance companies and spiralling into depression.

PAIN

To this day nobody knows why I crashed. I can remember the brutal thud, so I must have hit something hard like a rock. But it’s impossible to piece together what happened. Later on I spoke with Skyler Howes, who now competes in the Dakar Rally. He was one of the first on the scene and stopped to help me. With off-road races and rallies there’s a compassionate time rule; any time you lose stopping to assist someone who’s been injured will be taken off your race time. Yes, it’s a race and yes, the other riders are your competition, but we’re usually out in the middle of nowhere at these events. You’d have to be a real arsehole to keep riding while somebody is lying on the deck.

Somebody’s life is worth a lot more than a race win or a trophy. There’s an understanding between us as riders that if you see somebody injured, you stop and help them regardless of what it means for your own race. That’s what Skyler did for me that day in Lucerne Valley. He didn’t see the crash itself; once he got there, I was on the ground and completely dazed and confused. When he later heard how serious my injuries were he couldn’t believe it. He called me and said, “You were knocked out and then you got back on the bike. It was the gnarliest thing I’ve ever seen. How are you not in a wheelchair?”

He says I made it about 100 metres down the road — with a broken neck! — but that I was all over the shop. Somebody else crashed in front of us, so I stopped to try and help him. But once I got off the bike I just laid down and started groaning in pain. He says my first worry was that I’d lost my GoPro. Then I started taking all my riding gear off. I was lying in the middle of the desert wearing nothing but my jocks. I don’t remember any of it. I’ve pressed him about it a few times, asking if he’s given it the “round the campfire” treatment and embellished the story a bit. But he’s dead serious about it.

If it really happened, then I must have a guardian angel. And I reckon I know who it is. When things like that happen, I think of my sister Min sitting up there keeping me safe. As far as I’m concerned, she played a big part in this whole thing. But even with her intervention I got so damn lucky. I’ll never buy a lotto ticket in my life, because I used up all my luck when I survived that crash. I was alive, the pain from the halo finally subsided, but I wasn’t out of the woods. In fact, there was a week of hell ahead of me. It was initially tough for me to comprehend the full seriousness of the injury. Apart from the halo I’d never been in serious pain, and I could still move my arms and legs. But I kept having the same conversation with the doctors over and over: “You’ll never ride a motorbike again. What were you doing it for in the first place? It’s a stupid sport.” If there’s one thing I’ve learnt over the years it’s that doctors do not like people who ride motorcycles. I’m not sure why, we keep them in a job.

The doctors looked through the scans and X-rays. Usually each vertebrae overlaps the next all the way down, but I’d bent my neck so far forward that it had basically inverted the bones in my neck. That had to be sorted before they could do anything, even surgery. So they put me in traction to slowly pull my head away from my body, to get my neck to stretch and then pop back the right way. They also worked out the best surgical option for when that was done, which involved fitting some rods in my neck. It was going to cost around US$500,000.

I wasn’t worried about the money, I’d carefully chosen an insurance policy that had me covered for this very situation. At least so I thought. When I lodged the claim for the money the insurance company went silent. Then they rolled out a clause that said the only race I was covered for was a running race. They said they had no idea I was going to be racing a motorbike, which was complete bullshit. I’d gone through a broker to get the best insurance I could have for those trips overseas. I had outlined exactly what I was travelling to North America for — to race a motorbike. And I wanted to be covered if I got injured on the job. It wasn’t cheap and the insurer happily took my money and told me I’d be covered. But there I was, lying in hospital with a broken neck being told, “If you look at Section Whatever and Clause 525.2 in Column C, it says we don’t have to pay for your surgery.”

I was devastated. My life was dangling by a thread, almost literally, and they were pulling this shit on me. “Sorry, sir, that’s how the policy works. We wish you all the best.” The harsh reality was that I didn’t have what was the best part of a million Australian dollars to pay for the surgery. I was doing all right for myself, but I wasn’t flush with cash. Two years earlier I’d been living in a caravan. I was still in the share house with Reggie. I asked the hospital what my options were and they told me that, without the surgery, the only thing I could do was stay in the halo for four months. I’d heal, but not properly. I’d be stuck in a wheelchair for the rest of my life. Forget ever riding a motorbike again. Even with the surgery, they told me not to even think about bikes. Whatever I did, my career was over. But at least with surgery I could live some sort of normal life.

Every little bit of it was bad news. Everything I’d worked for was gone. I was laying there with a broken neck and being kicked in the balls over and over. The insurance was screwing me over. I was uncomfortable. I was facing a choice between a wheelchair and financial ruin. The last thing I needed was these f—king doctors telling me over and over and over that I was never going to ride a bike again. It didn’t help my process in dealing with what was going on, it didn’t help my try and work out a way out of this mess. I found myself getting angry every time I was told I’d never ride a bike again. I’d tell these doctors to shut up and get out of my room.

It was hard to get information back to Mum and Dad in Australia. They’d initially only heard about the crash via something they spotted on Facebook, a post from someone saying, “I hope Toby Price is okay”. Then someone else commented on it with, “It looks like he’s broken his neck.” They were panicking. Dad tried to call me and then tried to call the team. After the longest hour of their lives, the team manager called Dad back to fill him in. Meanwhile, I was about to be incapacitated by the traction process and I was spiralling into depression. I called home and said, “Hey, I’m in big trouble here. I’m going to either be in a wheelchair for the rest of my life, or forever working to pay off a crippling debt because the insurance company has done a runner.”

Mum and Dad scrambled to get over to Palm Springs and arrived just as I was being put into traction. When they popped their heads over the top of the bed and into my line of sight there was initially this comforting feeling of seeing familiar faces — but those faces told me a story I didn’t want to hear. I hadn’t sat up, I hadn’t showered, I had barely moved since the crash. When I saw Mum and Dad’s reaction to me laying there with this halo screwed into my skull, it hit me harder than ever that I was in a bad way. The traction meant I was stuck on this bed, flat on my back, with what looked like a Meccano set behind me. There was a V-plate that was screwed to the halo, which was connected to a pulley and a rope and they’d hang weights off it.

Once I was in traction the really dark thoughts set in. I still didn’t know what was going to happen with the insurance, but did it really matter? If I wasn’t going to be able to ride a motorbike anyway, what was the point? What was the point of even being alive? All I wanted to do was race motorcycles. Why bother dealing with all this shit with the insurance company? I started to think that maybe it would be better if someone just gave me a needle that put me to sleep. The sort of sleep you don’t wake up from. They were deep, dark thoughts. I’d been teetering on the edge of depression and suddenly I found myself firmly in its grip. My thoughts were as black as they get. I wanted to turn the lights out permanently.

It wasn’t all about riding bikes. There was an underlying feeling of guilt on top of the physical and mental anguish. I was putting my poor parents, who had been through so much, through more shit. As a family we were still dealing with losing Min, even though it was two years later. I knew how hard it was for my parents to look after Min when she was alive. And here I was lying in a bed, facing a life of needing a similar sort of care. Maybe, I thought, it would be better for them if I wasn’t around. They could just get on with their lives and not have to worry about wheeling me around. I’d spent the last 26 years causing them stress and grief.

All I could see now was that I’d be in a wheelchair and they’d have to go through all the pain and problems again. I thought about how selfish I’d been to get myself into this situation in the first place. And now I was going to be even more selfish and need my parents to take care of me for the rest of their lives, 24 hours a day, wiping my backside, showering me, feeding me, putting me to bed each night. Enough was enough, I didn’t want to do this to them. Of course, my parents didn’t want me thinking that way, but I was overcome with depression. I was at my lowest. I wanted to die. As it turned out, having my parents there was what saved me. The reassurance of having them by my side eventually took over. Their attitude through another setback was unwavering. They handled it the same way they’d handled everything else; we’ll find a way, we’ll get through it. I think I even cracked a smile when Mum joked, “Don’t worry about us, mate, we’re experts at wheelchairs.”

They continued the fight with the insurance company about paying for the surgery. One of the nurses was particularly nice and told us that, from what she could see, we were being ripped off. She even called the insurance company herself, which she probably got in strife for with the hospital. The company sent an assessor over to the hospital to interview me, but I barely remember it happening. According to Mum and Dad, it didn’t go all that well. There were countless calls and emails and, in the end, the insurance company just stopped replying. They stopped calling back. They were happy to wipe their hands of me. It was devastating, but we didn’t have the energy to keep fighting them. We had to come up with a solution.

Between dealing with the insurance company, Mum kept herself distracted by marvelling at how run down the hospital was. As a trained nurse, she knew a thing or two about hospitals and she couldn’t believe what she was seeing. She couldn’t believe the waste. As well as the three breaks in my neck I’d also broken my thumb. When Mum first walked in she thought I’d broken my whole arm. I was bandaged from the thumbnail to my armpit. At one point, after my arm was redressed, I complained the bandage was a bit tight – so they cut it down the middle, threw it in the bin and grabbed a new one. They could have just unwound the bandage and tried again. Mum was gobsmacked. I think it was her way of dealing with the grief. She took photos of everything she saw, from dead flies on the windowsill to dirty floors to whatever else was going on.

The hospital was ready to operate, but they weren’t going to do a thing until they got their half a million bucks. They weren’t trying to rush me out, so to speak, but if the surgery wasn’t going to happen, they didn’t want me taking up one of their rooms for too long. They just wanted to know what we wanted to do. It didn’t take us long to realise Australia was our best option. The moment I could get my feet on Aussie soil, everything would be taken care of. The healthcare system would kick in and I’d be able to get the surgery I needed to at least avoid ending up in a wheelchair. The problem was we were a 14-hour plane ride from home, and commercial airlines aren’t set up to transport people with a life-threatening neck injury.

We looked into my private health cover in Australia to see if they’d cover the cost of a private air ambulance back to the country but had no luck. And paying for that out of my own pocket was worse than paying for the surgery in the US; it was going to be well over a million bucks. We were between a rock and a hard place and we were getting more stressed by the day. Our only option was a commercial flight. Given that Mum was a nurse, or at least had been once upon a time, she would be able to provide me with some basic care on the way. The next step was finding an airline that would agree to this outrageous plan.

CareFlight, an Australia charity that specialises in medical air transport, reached out to see if they could help. Luckily for me, they had some staff members who were into riding bikes and had heard what was going on. They started looking at ways to get me back home. Their first idea was to try and fund a private charter home, but the expense was huge. I didn’t want to burden a charity that ran off donations with something like that. All I’d done was fall off a motorbike, I didn’t deserve that kind of special treatment. I asked if they could just put me in contact with someone who could help get me onto a commercial flight. I was willing to take that risk; I was happy to sign as many indemnity forms as needed to get onto a normal plane and get me home to have this surgery.

There was two days of solid work making calls and sorting out paperwork. In the end Qantas agreed to bring me home, as long as I signed my life away and they couldn’t be held responsible for what happened if the plane hit turbulence or something like that and I was left in a wheelchair. I didn’t care. I finally felt like people were trying to help me get home and get fixed up. ■

Endurance: The Toby Price Story, co-written with Andrew Van Leeuwin and published by Penguin ($34.99rrp), is out now at all good book stores

For the full article grab the May 2022 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.