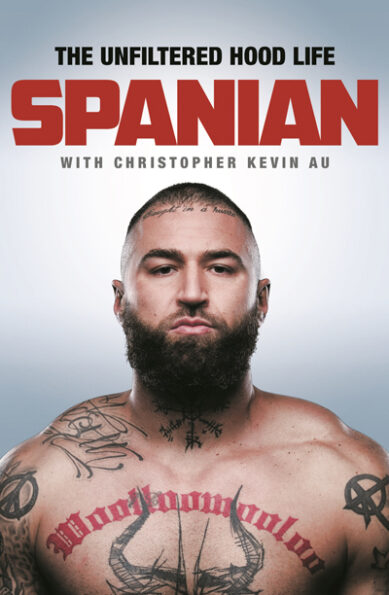

How a young, inner-city kid went from being a criminal and longstanding resident of jails across New South Wales to hip-hop star and social media sensation…

After a decade-long string of stabbings, ram-raids, drug runs and the notorious high school siege — not to mention heroin dependency and 13 years wasted behind bars, the dude they call SPANIAN is finally focusing on remaining a free man. The now viral hip-hop star was in a vicious vortex of crime, violence, incarceration and drug addiction and heading for total annihilation when the artist within emerged — not just giving his life new meaning and purpose, but damn well saving it.

For years throughout the Sydney social housing enclaves of Redfern, Waterloo and Woolloomooloo, Spanian earned a reputation as one of the city’s most flagrant crooks — armed with a box cutter in one hand and a syringe in the other – consequently serving several sentences at prisons across the state. However, while in jail, music and books became an unlikely lifeline and since being released from Bathurst Correctional Centre in 2017, with newfound purpose, Spanian has found fame and a sprawling, worldwide audience through hip-hop and his magnetic social media presence.

Whether it’s his uncompromising raps or viral Instagram and TikTok reels, he has evolved from an underground artist to a full-blown counterculture icon. Through music, he’s found an outlet for his unfiltered tales of street life, violence, the criminal justice system, prison life and the gritty underbelly of inner-city Sydney. Here, in this edited extract from his first book Spanian: The Unfiltered Hood Life, he gives us an insight into his time behind bars and life in prison.

I used to do bag snatches at the casino from the back exit on Pyrmont Street. It was only a short run from there to my Mum’s place. During the day, I’d climb into Mum’s building and down the fire stairs. I’d keep the fire exit door ajar with a milk crate or some other sturdy object. After robbing someone, I’d run back to the fire exit and as I jumped through the narrowly open door, I’d kick out the milk crate, which would shut the door and lock it to anyone who was chasing me. Then I’d go through the fire stairs to Mum’s unit and pretend like I was visiting her, and wait until the coppers left the area.

One day, I was looking for people to rob on Pyrmont Street when I saw an Asian bloke with a cad bag. They have a leather strap and you hold them in your hand — they’re strictly for rich c—ts. The Asian bloke was smiling, so I thought he had a big win at the casino. Around the casino you always want to rob wogs or Asians, as they have the most money and they can’t run for shit. Aussies spend their money on alcohol and never have any cash, so I never even bothered with them.

And so I picked my target, approached swiftly and snatched the bag. I’d loop my arm through the strap and pull hard to ensure a clean snatch. If I didn’t pull hard enough, the person could hold onto the bag and get dragged along the asphalt, and then I’d be facing a bigger charge. So I swooped in, got a clean snatch and was on my way. The Asian bloke chased, because all public heroes chase. I got to Mum’s building, kicked out the milk crate, and the fire exit door shut. Success.

I got to Mum’s unit and knocked on her door. Knock. Knock. Knock. Nobody answered. I waited a second longer and knocked again, this time more frantically. Knock! Knock! Knock! Knock! Knock! Still nothing. I ran back to the fire stairs and went up a level to a unit where two girls I knew lived. They weren’t home either. I ended up hiding in the garbage room, but the police surrounded the building and arrested me among the bins and fruit flies. The worst part? The bag didn’t even have that much cash in it, so my cad bag theory was wrong that one time. I was sent back to Cobham [Juvenile Justice Centre].

These sentences were usually easy by now, but this time, I was hanging out for heroin. It was the worst feeling ever, like a potent cross between a severe flu, extreme exhaustion and insomnia. I’d go days without sleep and have little flashes of blacking out during the day. I told the nurses and they took great care of me. They gave me Valium and big bottles of cordial to keep me hydrated. Some days I wouldn’t have the energy to leave my cell, and they’d bring me a television, even if I didn’t have enough points for one. After a while, the colour in my face reappeared and I started to feel normal again.

After three weeks in Cobham, I celebrated my 18th birthday. They gave me the usual gift package: a bag of lollies, a beach towel, a pair of thongs and a Nike cap. The next day, the police arrived at my cell. “You’re 18, you’re going to jail,” they said. If you’re serving a juvenile sentence, you can stay in boys’ homes well past your 18th birthday, if you behave. Even at Cobham, there were 19 and 20-year-olds. But since I had a track record of non-participation, they didn’t let me stay at Cobham.

That would be my first time in adult jail, which I’d already heard about from the older boys. A lot of people actually preferred adult jail because you could smoke there. I wasn’t a smoker so I was happy at Cobham, but I didn’t care either way. They put me in a cop car and drove me to the nearest police cells, which were at Penrith Local Court. I was entered into the system and they gave me my MIN, which stands for Master Index Number. That number would follow me for my entire jail career that lasted well over a decade: 375854.

I took off my navy blue Cobham clothes and was handed prison greens and these shitty white shoes with straps on them; they looked like shoes off CSI or something. Just putrid clothes and putrid shoes. They put me in the cells underneath the court, which is where they locked up all the lads who were refused bail. It was mainly twenty-somethings and 30-year-olds straight off the street. There were eight people in my cell, with mattresses tossed on the floor and one toilet in the middle. There was a pack of cards, so I joined in on some card games. We were in those cells for two days.

Until that point, I’d never spent more than six hours straight in a cell unless I was sleeping. There was no such thing as a full day inside at juvie, but this was two days straight. Oh, and the food. F–k me, the food was shit. It came on these metal trays that’d been frozen for months and then reheated and delivered to us. It was just lukewarm slop – unidentified meat and zombie vegetables. You know how shit hospital food is? Well, that’s 20 times better than what jail food was back then.

After two days, three screws walked up to the cell: one with the keys to open the cell, one with a bunch of handcuffs on his wrist and one with a book. One by one, they called the inmates by their last name. Everyone else knew the go, but I’d never done this before. And so I watched as inmates stood, went to the cell door and put their wrists through the slot where our food was delivered. They were handcuffed and then sat back down. The screw called my last name and I did the same. “What’s your MIN number?” he asked. “I don’t remember my MIN number,” I replied. The screw looked up at me, and saw that I was just an 18-year-old. He was understanding. “You’ve got to remember it. Your MIN number is 375854, okay?”

I nodded, and they put the handcuffs on me. After all eight of us were done, they opened the cell and we were marched one by one into what looked like a f–king fridge truck. It was white on the outside and caged on the inside — just raw metal and bars. Four of us sat on one side and four on the other. It was so squished back there, our knees were touching. When they shut the door, it was almost pitch black. The only light came from these little windows that were less than 10cm high at the top of the truck. If you stood up, tilted your head 90 degrees and pressed your cheek against the ceiling, you could maybe see the street outside, but not much because the windows were so scuffed. The windows only let in a bit of light so we could tell if it was day or night.

The truck started; I could feel the soft rumble of the engine, then I heard the fan turn on, and then a little light flickered in the middle of where we were seated. The truck started driving towards what would be my first adult jail: Parklea. Still to this day, my most hated part about jail was transit in those f—king trucks. They were horrific.

When I got to Parklea, I remembered visiting Uncle Tony there a few years before, when I was just a kid. Now I stepped into reception as an inmate. It felt like a very natural progression. At Parklea, everything was so much bigger than the boys’ homes. There were about 15 reception cells and they were so full. The eight of us were put into one. Then we had our photo taken, our fingerprints done and received our care package. We got two pairs of pants, two shirts, two jumpers, two pairs of shorts, three pairs of socks and one pair of shoes. After that, they sent us to the reception wing for Parklea, which was called 1A. At Parklea, all of the cells were two-out. In juvie, all of the cells were one-out and being able to stay with a friend in a two-out was a privilege. It was the opposite in jail — we all shared cells and a one-out was uncommon. The cell was very dirty and there was no television, no radio and no pillow. Just a stained mattress and creaky, rusty shelves. I shared my cell with one of the c—ts who was on the truck — an older Koori bloke from Campbelltown. He was in his late thirties and I could tell he wasn’t a career criminal or anything like that. He was a really nice guy.

“This is your first time in jail, right?” he asked.

“Yeah, I came from juvie,” I replied.

“You’ll be all right, brother,” he said. “Let me just tell you one thing, and never forget it: never do something for someone who wouldn’t do it for you. Do you know what I mean by that?” “Yeah. If someone tells me to do something, don’t do it,” I said. “No,” he replied. “If someone asks you to do something, you can do it. But you just need to ask yourself a question first. If someone asks you to chuck something in the bin, what would happen if you asked them to chuck something in the bin? That’s how you know.”

That was the first ever lesson I got in jail, on my first ever night, with my first ever cellmate. And it was one of the truest things I’ve ever heard. If somebody today asked me to give them advice for jail, I couldn’t think of a better answer. And not just jail, but for life in general. Yeah, it was a very good life lesson.

The next morning at 8.30am, I got put into the concrete yard. In juvie, I’d spend this time doing activities with kids who were wide-eyed and healthy. In jail, everyone was just scummy, smelly, depressed and hanging out for heroin. Everyone had body odour, every second c—t didn’t shower, and you looked at people’s heads and could see big snowflakes of dandruff. I hated it. And it didn’t help that we were in the reception wing, so everyone had only been inside for two to three weeks. That meant that nobody had enough money for a buy-up, where you could purchase better food, toiletries and clothes. So everyone was starving, complaining, and wearing the bare essential boob clothes, which is what you call jail-issued clothes.

At midday, we went back to our cells where they served us lunch, and at 1pm we went back into the yard for two hours. At 3pm we went back into our cells, and that was it. There were no games, no activities, no sports; there was nothing. Oh, except for cards. That was the extent of activity at Parklea — playing card games. Oh, and there were cigarettes. At reception, they asked if you smoked and even though I didn’t, I was told that I could trade tobacco for food. So I said that I smoked, and I was handed a yellow pouch of Drum and some Tally-Hos. Purely out of boredom, I started rolling cigarettes in my cell and smoking. Jail was so bad, I’d have probably doubled my sentence just to do it in juvie.

Within the first week at Parklea I also learned about my classification. Let me explain something to you — there was a classification system based on your criminal history and record in jail. “A” meant you were a high-security inmate, “B” meant you were a slightly less high-security (but still high) inmate, and “C” meant you were a low-security inmate. There are 27 jails in NSW today, and I’d say half of them are minimum-security prisons for people with a C classification. Some of these jails are on farms, some of them have inmates with full-time jobs, some of them don’t even lock the inmates up. There was also an “E” classification, which was for anybody who’d escaped or attempted to escape. “E” meant you were a high-security inmate forever. There was no way you could progress out of that classification, no matter how good your behaviour was. It didn’t matter if you had one day or 10 years left, you were “E” for the rest of your life.

I was told that I was an “E” classification inmate. Wait, what? Since when? Okay, rewind to two years prior when I was 16 years old, to a day I was at Kings Cross McDonald’s with my girlfriend. We were queuing up and I was thinking about the Quarter Pounder and McNuggets I was going to order.

“Anthony,” someone behind me said. I knew it was coppers because everybody else called me Spanian by then. I turned around and, sure enough, there were two officers standing there. “Mate, you’ve gotx warrants out. Let’s walk to Kings Cross cop shop,” one of them said. By now, the coppers were on either side of me, holding me firmly by each of my arms. I knew I had warrants out, but I acted innocent. “What’s going on?” I asked. “We don’t know yet, but you’re on the system. You’ve got warrants. Some detectives want to talk to you,” he replied. “Far out, all right. Let’s go then,” I said.

As we calmly walked out of Macca’s, I felt their grip loosen on my arms and I pulled away and sprinted off. I ran down the stairs to Woollo, jumped a fence and was gone. A few weeks later, I was arrested. But whatever charges I had on those warrants, I had an additional charge for escaping police custody, and that’s where the “E” classification came in. Because of that, I wasn’t allowed to participate in the young offenders’ programs in jail. There’s a nice jail called Oberon for young offenders where you go camping and do ropes courses, and I wasn’t allowed there. No work release, no training for work, no training for the community. From the age of 18 I was put in maximum-security prisons with the most violent offenders and doing 19-hour lock-ins.

From that day on, there was nothing for me to work towards in jail. Even in the moment they told me, I didn’t understand what it actually meant. It was only later that I realised the full implications of the “E” classification. That one day at Macca’s would be one of the most defining moments of my entire life. ■

This is an edited extract from The Unfiltered Hood Life by Spanian (with Christopher Kevin AU) published by Hachette, $34.99rrp, available at all good book stores. For more go to spanianofficial.com

PHOTO SUPPLIED BY AUTHOR

For the full article grab the January 2022 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.