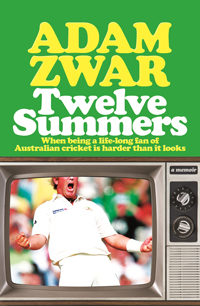

Most of us can measure our lives against major events, and for actor and writer Adam Zwar every memorable moment in his life is tied to cricket. So much so, he’s written a book about them all, titled Twelve Summers. And with The Ashes 2021/22 series currently in full swing, in this edited extract from his new tome, Adam shares one of his fondest memories during STEVE WAUGH’s greatest Ashes moment in the 2002/3 series…

In early November 2002, as the Australian team prepared for the 2002–3 Ashes series, Steve Waugh had a feeling the selectors wanted the series to be his last. I had a feeling too. Possibly, the whole of Australia did. The rot had set in eight months earlier when the selectors, headed by Trevor Hohns, dropped Steve Waugh as Australia’s one-day captain. Hohns had been sensitive about exactly where to let Waugh know he’d been axed. He thought it would be a little harsh to give him the bad news in his hotel room on the day of the 2002 Allan Border Medal. So he had tried to do the deed the day before in Devonport, as Waugh waited to go in to bat for NSW in a limited-overs clash against Tasmania.

Hohns asked the padded-up Waugh for five minutes of his time. Waugh explained he was next in. A disappointed Hohns suggested they catch up in Melbourne the next day. As Hohns made his way to Waugh’s Melbourne hotel room on that February morning, Allan Border admitted to feeling physically ill. He was on the selection panel and knew what was about to happen. Australia had missed out on the final of the 2001–2 World Series Cup Tri-series versus South Africa and New Zealand and the selection panel was unanimous in its decision that Waugh had to go.

Hohns sat down and asked what he wanted to talk about first, Tests or one-dayers. Waugh said, ‘Tests’, and that part of the conversation was straightforward, as Waugh’s test spot wasn’t under immediate threat. Then Hohns moved to the one-dayers and told Waugh that the selectors didn’t think he was one of the top six one- day batters in the country. Hard to believe they were referring to the same man who, just two years earlier in the ’99 World Cup, mounted the greatest rear-guard effort in the history of limited overs cricket.

The decision was final. Waugh had played 325 One Day Internationals over 16 years. As captain, he’d taken Australia from seventh to first in the one-day rankings. And now his white ball career was over. Waugh would later say he was ‘stung’ by the clinical efficiency of his sacking. The media coverage that followed was so extensive that Waugh’s six-year-old daughter, Rosie, started calling her father ‘Steve Waugh’.

I met Steve Waugh once. It was after I’d finished a performance of a play in Brisbane and had joined some mates at a nightclub overlooking the river. There among the heaving ’90s throng was the Australian men’s cricket team having their final get-together before leaving for the ’96 World Cup. Damien Fleming was at the bar. Ricky Ponting left early with a grumpy look on his face. I stood at the urinal between Paul Reiffel and Michael Slater. Then, as I walked back into the club, I saw Steve Waugh having a quiet drink with some support staff. I introduced myself and he couldn’t have been more decent. I had several questions I wanted to ask — why was his first nickname ‘Drobe’ and how did he transition to ‘Tugga’? Why does he talk to himself while he bats? And when he first saw a cricket protector at the age of seven, was it true he tried to put it on his knee? But I refrained. I just wished him luck and made an uncharacteristically dignified exit.

When I got home and looked in the mirror, I saw that in my rush to leave the theatre, I’d forgotten to take off my make-up. It wasn’t white restoration make-up, but there was a substantial amount of base, eyeliner and rouge. Make-up on men was not a thing in those days. Well, not in Brisbane. And certainly not when talking to the Australian men’s cricket team. So kudos to Waugh et al; they had every reason to take the piss, given the era and the hyper-masculinity of their workplace, but were decent enough not to.

THE FIRST FOUR

Steve Waugh needed a career resurgence to cement his spot in the Test team, but his scores on the 2002 tours of South Africa and Pakistan were mostly mediocre and it seemed selectors, the media and some of Waugh’s teammates were convinced the 2002/3 Ashes series would be his last. Even Richie Benaud said he was a ‘condemned man’. It was just the right amount of adversity to bring out Waugh’s best. But the fightback didn’t start well. He scored 7 and 12 in the First Test in Brisbane, which Australia won by 384 runs. In the Second Test in Adelaide, which Australia won by an innings and 51 runs and where Ponting scored his second century in two Tests, Waugh managed 34.

When Waugh arrived for the Third Test in Perth, Hohns visited his hotel room again to tell him that the fifth Ashes Test in Sydney ‘might be a good place to finish’. Waugh told Hohns he wasn’t sure. According to Waugh’s book, the conversation had been low-key and amicable, but Hohns spoke to the media immediately afterwards, saying, “At the moment, Stephen has our support until the Sydney Test.” Waugh knew that if ‘Stephen has our support’ wasn’t the final nail in the coffin, then ‘until the Sydney Test’ certainly was. After modest scores in Melbourne, the equation for the Sydney Test was simple — if Waugh didn’t score a century, his career was over. Every sports report on every network news bulletin led with ‘this will most likely be’ or, more generously, ‘this could be’ Steve Waugh’s last Test.

THE LAST BALL OF THE DAY

I watched Waugh’s do-or-die innings in the Fifth Test from the offices of the Sunday Herald Sun, ignoring my work and pacing up and down in front of the TV. England had made 362 in the first innings, and when Langer mistimed a hook shot and was caught in the deep, Australia found itself in trouble at 3–56. Instead of taking his time walking out to the middle for what might’ve been his final Test innings, Steve Waugh ‘sprinted’ out there. He said he had a feeling there’d be a lot of applause and wanted to get onto the ground quickly, so he didn’t ‘soak up too much of that goodwill and forget about the job at hand’.

Waugh started his innings efficiently, punching the ball all over the ground and giving away no chances. When Waugh was in his 40s, Andrew Denton came out onto the ground with the drinks. That threw me, but it didn’t throw the commentators enough to mention it. Turned out Denton had paid a couple of thousand dollars at a charity auction to be the assistant coach of the team for a day. And it just happened to be that day.

In the documentary Perfect Day, Denton describes serving Waugh Gatorade and the ensuing conversation. “I said, ‘How you going?’ And he’s taking his helmet off and it’s dripping with sweat. He said, ‘I’m enjoying myself.’ And he has the drink and I’m thinking, ‘What’s the protocol here? Are you meant to say something?’ So, as I left, I just said, ‘Don’t be home before six.’ And wandered off.”

Waugh continued to play a chanceless innings. He was timing the ball well and his big shots kept finding gaps. But when Damien Martyn and then Martin Love were dismissed, the capacity crowd started to grow edgy. They wanted a century from Waugh and the worst-case scenario was that he would run out of batting partners. Or get run out. Gilchrist had only been in the middle for a short time before Waugh called him through for a single after hitting the ball firmly to mid-off. Waugh scampered, it was tight, and the fielder threw down the stumps at the bowler’s end. The replay showed Waugh was well in, but the crowd was restless as it waited for the third umpire’s decision. And it retained its nervous murmur even when it learned Waugh was not out.

Everyone was on tenterhooks, and it was the same in the offices of the Sunday Herald Sun. Most of the staff were standing at their desks, watching one of three televisions situated around the office, arms folded, shifting weight from foot to foot. Phone calls were ignored. At around 5.45 pm, Waugh brought up his 10,000th run in Test cricket with a slashing cut shot to the boundary. He was the third man to do it — behind Sunil Gavaskar and Border. The crowd was on its feet. Whatever was happening in the middle of the SCG, those 48,000 spectators were a big part of it.

By 6pm Waugh was on 80 — still not enough to avoid the axe. I was dreading hearing the line from the commentary box: ‘And it’s goodbye to our New South Wales and Victorian viewers as they go to the news.’ It would have to be a big event for them not to go to the news. I’d only known broadcasters to delay it when a match was nearing a dramatic conclusion, not when a guy was trying to reach his century. Then Tony Greig calmed our restless hearts.

‘We’ll be staying with the cricket until Steve Waugh either gets his 100 or gets out,’ he said. ‘That’s at least what we’ll be doing.’ That was big. The delay to the 6pm bulletin legitimised the event as something of national significance. Most of the country knew the equation — a century means Waugh stays. Anything less, and he goes.

For the final over of the day, Waugh was on strike. He was on 95. Off spinner Richard Dawson’s first two deliveries hit Waugh on the pad. The third ball he blocked. ‘The entire team, and everyone related to the team, gathered on the balcony and there was just dead silence,’ Denton said in Perfect Day. Waugh struck the fourth ball through cover for three. It was a solid shot, but problematic because it put Gilchrist on strike with just two balls to go. Gilchrist needed a single so Waugh could face the final ball, bring up his century and get the selectors off his back. He didn’t want to have to sleep on it overnight and try to get the job done the following morning.

Gilchrist said he had visions of stuffing it up and being booed off by 40,000 people. Instead, he glanced the ball past square leg for a single and the crowd cheered like he’d saved someone’s life. Then everyone got nervous all over again. One ball to go. Waugh was on 98. Hussain held up proceedings by moving the field and talking to Dawson. It was second-rate gamesmanship. The crowd booed and Waugh gave him a dirty look. Hussain would later describe the look as ‘utter disdain’. Dawson bowled, a fast ball, well-pitched. Most would’ve defended, but Waugh’s wrists were lightning fast and he drove through extra cover.

Bill Lawry: ‘He’s gone for it. There it is!’ The ball skidded across the SCG turf and into the boundary rope. It was skill. It was also a miracle. Waugh had scored his 29th Test century, equalling Sir Donald Bradman’s record. Bill Lawry: ‘A great moment in the history of Australian Test cricket.’ Meanwhile, on ABC Radio, the silky voiced Jonathan Agnew took the emotion to another level. ‘That. Is. Ext-rah-ordinary. And Steve Waugh, a man of little emotion, can barely restrain himself now. His helmet’s off. Oh, he’s waving his bat. Alec Stewart shakes his hand. You could not have scripted anything more remarkable than what we have seen here this afternoon.’

There was a sustained roar from the crowd as Waugh held his hands aloft. Everyone in the Sunday Herald Sun newsroom was in tears. And, weirdly, I received text messages from all around the country simply because I was the person my friends and family thought of when they thought of cricket. ■

Twelve Summers by Adam Zwar, published by Hachette Australia $33rrp, is available now

By ADAM ZWAR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adam Zwar is an actor, writer and voice artist. He is the co-creator of the Australian comedy series Squinters, Lowdown and Wilfred, created the Channel 10 comedy series Mr. Black and the factual series Agony Aunts, Agony Uncles, The Agony of Life, The Agony of Modern Manners and Agony. He also presented and produced the cricket documentaries Underarm: The Ball That Changed Cricket and Bodyline: The Ultimate Test, and hosted the podcast 10 Questions.

For the full article grab the January 2022 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.