A new book by renowned motoring historian Luke West celebrates the stories of the greatest ever Aussie drivers across the decades. In this edited extract, he takes a look at the greatest and most popular figure in Australian motor racing history bar none – and the most successful driver ever in the Bathurst 1000. The one whose on-track success was backed up by a charismatic personality that contributed to cult-like hero worshipping. No-one did more to attract attention and fans to motor sport than the man in #05 – PETER BROCK …

Born on February 26, 1945 in Melbourne, Victoria, Peter Geoffrey Brock was Australian motor racing for many Aussies, drawing more people to the sport than anyone before or since. For those reasons alone he’s worthy of Immortal status. Brock paved the way for the Bathurst 1000’s incredible growth, ditto local V8 touring car racing’s success in recent decades. While the early Australian touring car heroes laid the groundwork, it was Brock as the most successful driver of the 1970s and 1980s who was instrumental in building Bathurst into the motor sport phenomenon it now is. His engaging persona created a following that gave Supercars racing the critical mass to become a major player on the local sporting landscape. Well-known racer and television commentator Neil Crompton, the man who had the unenviable job of delivering a eulogy at Brock’s funeral in 2006, made his Bathurst 1000 debut in 1988 courtesy of the nine-time Great Race winner. Crompton eloquently summed up Brock’s contribution to the sport: “If you think back to the early 1970s, his rivalry with Allan Moffat built the Holden versus Ford platform,” Crompton explained. “And in those days, as I recall as a young bloke, they actually did describe the cars as ‘supercars’. That was a colloquial description of them, because three big manufacturers [including Chrysler] were all trying to one-up each other with bigger/better/faster cars. Peter was a white knight in that whole stoush. He was the all-Aussie young bloke with the good looks in the GTR XU-1. And his rival, Allan, was Canadian… but it sounded like an American accent to us. Regardless, their battles made for great theatre.”

This rivalry kept the crowds and the television audience coming back for more. Crompton says Brock’s general media magnetism saw him quickly become Australian motor sport’s front man, helping the public make sense of an often misunderstood and misperceived sport: “With his engaging personality he was something of a pied piper, I reckon,” Crompton continued. “He drew lots of interest to the sport. The real trick with Peter was that he was such a bright star — and you get these people from time to time in sport, entertainment and politics — and they attract a lot of interest from more than within their own postcode. He was not just a car racer who won races; he was media friendly, especially with the nonspecialist media. He could speak enthusiastically about more than just racing, which made him a true ambassador.”

Long-time and former V8 Supercars Australia chairman Tony Cochrane suggests Brock’s contributions to what we now enjoy were enormous, including acting as a positive role model for today’s teams and drivers: “Peter was something special for two reasons quite beyond his racing record. First, he was one of the first people to recognise and work at corporate involvement in the sport. Second, he was so fan friendly. He set the scene for our category that drivers make themselves as accessible as possible. Still today our fans can wander around the paddock and get up close and personal with the teams and drivers and cars. There is not a lot of professional motor sport at our level where fans can do that, so I really do believe that Peter by his very nature, his friendliness and openness set the tone for drivers who followed in his footsteps and that approach is still very much alive.”

The road to greatness began on the family property at Hurstbridge, north-east of suburban Melbourne, where Brock and his three brothers honed their car control skills charging around in an old paddock basher sans bodywork. They had chopped it off with an axe to lighten it and make it go faster. Brock made his racing debut in late 1967 aboard a Holden-engined Austin A30. Its ungainly but distinctive looks, along with speed and results it had no right posting, helped make the 22 year old a standout. Brock soon came to the attention of Holden Dealer Team chief Harry Firth, who called him out of the blue to invite him to join the squad for the 1969 Hardie-Ferodo 500 at Bathurst. He and veteran Des West steered their Monaro GTS 350 to third place on a day teammates Colin Bond and Tony Roberts emerged victorious, which ensured he was invited back the following year when the squad switched to Torana GTR XU-1s. In fact, Brock would race under the HDT banner in various guises for 16 of his first 19 Bathurst classics.

During this time, he chalked up his famed nine Great Race victories — a win rate of 45 per cent. The first win came aboard an XU-1 in 1972, the day Brock became a household name, driving solo in wet conditions that suited both the car and driver. He unexpectedly trounced red-hot race favourite Allan Moffat in his factory Ford Falcon GT-HO Phase III. He and Doug Chivas nearly repeated the feat in the dry the following year, except that Chivas was instructed by Firth to maximise fuel range and their XU-1 ran dry before it could reach the pits, having attempted one lap too many in the stint. Brock’s next major achievement was winning the 1974 Australian Touring Car Championship using an XU-1 and then the brand new V8- powered Torana SL/R 5000.

Tiring of being under Firth’s thumb, Brock jumped ship from the HDT for 1975 and beat Firth and the HDT at their own game at Bathurst that year in a privateer Gown-Hindhaugh L34 Torana he shared with Brian Sampson. When Holden sent Firth into retirement for 1978, Brock was brought back into the HDT fold, winning the 1978 ATCC then dominating at Bathurst that year and next in A9X Toranas. His 1979 Hardie-Ferodo 1000 triumph stands as the most dominant victory in event history, winning the race by six laps and setting the lap record on the 163rd and final tour of the 6.17 km circuit. This had previously been unheard of. Brock was truly at the height of his powers that year, winning the gruelling Repco Round Australia Trial to prove he was just as at home in rallying as in circuit racing. He would later tell journalists he considered this to be his greatest achievement.

He took over running Holden’s factory-supported touring car efforts under the HDT banner in 1980, a year he won his third and final ATCC crown and a third Bathurst on the trot for himself and Jim Richards. This time he and Richards had their work cut out, recovering from an early race incident that could easily have put them out of the running; yet, such was the charmed life he led at that point, no obstacle or setback seemed to hold him back. He didn’t win Bathurst in 1981, but it was merely an aberration. Another threepeat was achieved from 1982 to 1984, this time with Larry Perkins. By this time Brock was also in the business of building hotted-up road-going Commodores through his HDT Special Vehicles company. The magic he and his crew created on the racetrack and for the road would give him almost mythical status among enthusiasts of Holden cars.

Away from the racetrack the freethinking Brock often marched to the beat of a different drum, and by the mid-1980s many aspects of his lifestyle were alternative or New Age. He believed in the power of crystals, which formed the basis of the Energy Polariser he fitted to his road cars to make them – according to the man himself — “run smoother and more efficiently”. General Motors- Holden did not subscribe to the same theories, and the two entities were soon on a collision course. Brock refused to back down, and it came to a head in 1987 and resulted in a messy divorce. In February Brock, his race team and HDT Special Vehicles were finally excommunicated from the GM-H church.

It was then on to Bathurst with an underfinanced and resourced team, in sharp contrast to previous attempts and in a year when the best Group A touring teams from Europe entered. The lead Mobil 1 Racing VL Commodore blew its engine at half distance and Brock jumped, as the rules allowed, into the second team car, but then the heavens opened and many of those super-swift Europeans didn’t give the drenched circuit the respect it deserved. He finished on the podium in third place behind two Swiss-entered Ford Sierras that were subsequently disqualified, which meant that weeks after the event Brock and his co-drivers were elevated to the win.

That victory was Peter Brock to a tee: against the odds; extraordinary recovery from setbacks; things somehow falling his way at the expense of others; but deserved, nonetheless. Everything he did seem to fall his way, although 1987 would prove to be a turning point: his circumstances, results and on-track fortunes all changed. Some of it was tied to no longer having the might of Holden behind him, some to the increased competitiveness and depth of the field. For so many years Brock was Holden’s poster boy with all of the technical resources behind him, but those resources came to be enjoyed by others. Fans were dismayed when he moved away from racing Holdens for three seasons. In 1988 he ran BMWs then Ford Sierras for the following two seasons, as did virtually every team. His Mobilbacked team raced Holdens for three subsequent seasons against the company’s official representative squad, Holden Racing Team, largely without success.

Throughout this period Brock’s many fans yearned for him to be brought back into the factory fold. Time heals all wounds, and after seven seasons in exile Brock was recalled to the factory fold for 1994 when aged 49. He disbanded his own team and became a hired driver again, relieved of the pressure and complexity of getting two cars onto the grid. For the next four seasons he was good for the odd race win, but his real value lay in PR activities. No driver had longer queues of fans waiting patiently for his autograph and no punter went home feeling unappreciated by their hero. He would sit for hours, sometimes into the evening, until he’d signed everything put in front of him. Fans never forgot this dedication and the interest he showed in each and every one of them. He had a knack for making everyone he met feel like they were lifelong mates.

Brock started out in racing as a scruffy larrikin and ended up the most polished performer in the business. Along the way he went through distinct phases, from hard-smoking junk-food lover to spiritual guru and vegan. He announced his retirement from the touring car/V8 Supercars scene in early 1997 and enjoyed a farewell tour to remember, with record crowds, competitive drives, occasional victories and, appropriately, a final Bathurst to remember. Partnered with Mark Skaife, who would take his place at HRT the following season, #05 led the 1000 for the first 50 laps until mechanical gremlins struck and put the pair out.

Brock all but disappeared from the racing scene for a few seasons but retained a high profile in projects outside motor sport. This included acting as an athlete liaison and motivator for the Australian Olympic team, various commercial endorsements, continuing his lifelong role as a road safety advocate and his charity work. Ever enthusiastic about applying his famous name to a racing-related venture promising grand things, he became the figurehead of an eponymously named squad owned by long-time entrant Rod Nash. He was even enticed to make the first of two Bathurst driving comebacks in 2002 in a bid to boost the commercial fortunes of that year’s incarnation of Team Brock, but the VX Commodore he shared with regular driver Craig Baird was never competitive and chugged home a limp-wristed 23rd. However, this time he remained active and visible on the racing scene.

“Of course, he did come back a couple of times to Bathurst as a driver,” long-time V8 Supercars PA announcer Barry Oliver explained. “So while we lost Peter as a full-time driver in the championship, he was still very much on the scene doing various bits and pieces. He got involved in teams and had other interests. Peter’s subsequent returns for Bathurst in 2002 and 2004 in a V8 turned out to be a promotional bonanza for the race and V8 racing,” Oliver recalls. “To me that was basically him saying, ‘I love this place and I love these cars — it’s a special place and they are special cars.’ And that’s a message he enthusiastically passed on to the general public.” That 2004 Bathurst 1000 outing ended worse than did the 2002 attempt. Brock didn’t get to drive the #05 HRT Commodore in the race after British co-driver Jason Plato crashed spectacularly early in the race. Thankfully, in between was a stellar outing in the second and final running of the Bathurst 24 Hour sports car enduro.

Poetically, his last race win at Mount Panorama was aboard a Monaro (where it all began in 1969), and he effectively farewelled the famous venue as a winner when partnered in #05 by Todd Kelly, Greg Murphy and Jason Bright. A few years later he was gone. On September 8, 2006 while driving in the Targa West tarmac rally, the Daytona Coupe sports car he was driving left the road outside Perth and hit a tree sideways. He was dead within a couple of minutes of impact, and the news swept quickly across the nation and headed bulletins for the next few days. The outpouring of emotion was intense, with fans making a special pilgrimage to Mount Panorama to sign the wall at Brock’s Skyline. There were many nationally held commemorations and services. That year’s Bathurst 1000 was held just five weeks later, with the 161-lap race virtually taking a back seat to the planned pre-race tributes and the awarding of the Peter Brock Trophy to the winners. Appropriately, his former apprentice Craig Lowndes, along with Jamie Whincup, received the trophy. The one piece of the puzzle missing for Holden tragics in this fairy-tale victory was that Lowndes was driving a Ford Falcon for Triple Eight Race Engineering and not a Commodore.

Like so many sporting heroes in the public eye, Brock’s personal life was complicated and often played out in the media. He was married twice during his 20s, and both times those relationships proved short lived. His long-term partner, Beverley McIntosh, changed her surname to Brock despite the pair never marrying. They were together for 28 years and had two children together, with the family unit including Bev’s son James from a previous relationship. James was the only one to follow Peter into racing, the pair collaborating on various short- term motor sport projects.

Bev and Peter’s relationship ended the year before Brock’s passing but, in contrast to his last partner Julie Bamford, Bev would remain in the media spotlight. She released her third book on her former partner in 2019 and the publicising of her literary efforts has contributed to keeping Brock’s name front and centre, as have numerous other books, a dramatised miniseries and a cinematic documentary release, among other things. The latter two were only possible given the Shakespearean nature of Brock’s life story, with themes including boy from humble beginnings made good; triumph and tragedy; fame and fortune; love lost; squandering of fortune; redemption; and the return of the prodigal son.

He was always the dashing racing car driver from central casting: women were drawn to him, and blokes at Bathurst got his face tattooed onto their torsos. Brock was also the personification of the much- loved Holden brand. In the 1970s GM-H commercials encouraged a parochial diet of “football, meat pies, kangaroos and Holden cars” that ran during telecasts of races he won. A few years later such advertising campaigns were fronted by Brocky, which served to sell cars while extending the reach of his fame beyond racing fans.

Peter Perfect wasn’t always so perfect, but his devotees were forever prepared to overlook scandals that would sink less resilient men. They were also forgiving of some disastrous career choices, such as putting his name to Russian-built Ladas. They flocked to racetracks nationwide to cheer him on regardless of what happened off the track.

Along with the aforementioned successes, Brock won nine Sandown endurance races, 11 other major long-distance races, two South Pacific Touring Car Championships and countless one-off events. He contested the ATCC for 25 consecutive years (from 1973 to 1997), winning 48 individual races amid his three overall titles and finishing runner-up on five other occasions. The King of the Mountain made 32 Bathurst 1000 starts between 1969 and 2004 and was inducted into the V8 Supercars Hall of Fame in 2001. He raced overseas sporadically, most notably via a trio of starts in the 24 Hours of Le Mans and its touring car equivalent in Spa, Belgium.

In the closing years of his life Brock tackled off-road adventures in the Australian outback in the name of publicising Holden’s SUV offerings. His energy and activities were boundless. I’ll give the final words on Brock to the man who speaks more eloquently about racing than any other, Neil Crompton: “That he influenced the behaviour of today’s drivers is terrific. But the real weight to his contribution is that he drew attention to the sport beyond our postcode. It’s easy to make a splash with the hardcore, but it is very hard to become a genuine household name. There aren’t too many people who have done that. He was probably the first guy — certainly in sedan racing, because we had Sir Jack [Brabham] in F1 — where you could mention his name on any street in Australia and everyone knew who he was and that he stood for lots of good things.” ■

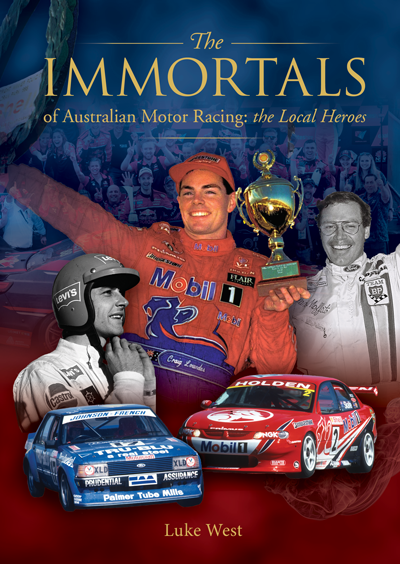

IMMORTALS OF AUSTRALIAN MOTOR RACING: THE LOCAL HEROES (Gelding Street Press, $39.99rrp) by Luke West is available where all good books are sold and online at www.booktopia.com.au

By LUKE WEST

For the full article grab the October 2021 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.