With huge crowds, multi-million-dollar TV rights deals and generations of household megastars the V8 Supercars have been a huge local motorsport success story for over a quarter of a century, turning it also into a globally recognised phenomenon. In this edited extract from his new book, LUKE WEST gives us a taste of the comprehensive and absorbing history he’s compiled about this uniquely Aussie sport…

Twenty-eight seasons and counting. That’s how long Supercars has been part of the Aussie motorsporting scene. Make that the Aussie sporting scene, as the Championship now commands a position that goes way beyond what any local racing class has previously managed. Supercars is a mainstream sport these days, with several race weekends on temporary street circuits drawing crowds in the hundreds of thousands, a big dollar TV rights deal and an all-pro field of teams with several of the drivers now household names. Of course it hasn’t always enjoyed its current lofty status. Nor has it always been called Supercars.

Most people know it by the V8 Supercars brand. Yet, in its first season, 1993, it was puzzlingly known by two names and derivatives thereof: ‘Five-litre V8 Touring Cars’ and ‘Group A’. Administrative body CAMS ultimately did a good job of shaping and overseeing the rules but showed its complete lack of marketing nous in retaining the unconvincing Group A label from its predecessor. Confusing much? Little wonder the architect of the class’s incredible growth, Tony Cochrane, the entrepreneurial Gold Coaster charged with transforming the sport, immediately rebranded it to V8 Supercars. Cochrane famously joked that the Group A name sounded like a blood disorder. Cochrane served as V8 Supercar chairman for over 15 years, overseeing its commercial success and bearing the brunt of criticism from motor racing traditionalists who lamented the sport’s entrepreneurial direction and his take-no-prisoners style. There were some growing pains and many hard-won gains, but ‘the V8s’ continued on an unabated upward trajectory for 20-odd years until plateauing in recent seasons.

The first quarter century or so can be broken down into several sub eras: 1993-96 were the pre-V8 Supercar years; 1997-2002 was the time of extraordinary growth; 2003–2012 constituted the Project Blueprint era; and 2013 onwards is the current New Generation (aka Car of the Future) period, when new marques entered, then exited, the fray. It’s been a wild and thoroughly intriguing ride throughout its history. Rarely have two seasons had much in common, besides the eventual Champion. Each of Jamie Whincup’s seven titles, for instance, had their own individual flavour with previously unseen dramas for him and his rivals. I have been a keen follower of local touring car racing since the late 1970s and recall with great fondness the excitement of the class’s gestation and birth.

I followed this via the specialist motorsport press and was sitting on the hill at Amaroo Park in 1993 when the category contested its first Australian Touring Car Championship race. I didn’t miss a race on television through the mid to late 1990s and eventually began writing for Auto Action in 2000, then V8X magazine. A few years later it was my privilege to call the action trackside over the PA system for fellow fans, first at Bathurst, then at each round across Australia as a contractor to V8 Supercars Australia. Next was an eight-year stint as editor of Australian Muscle Car magazine, which examined the cars that won the early titles and Great Races. Now I feel incredibly fortunate to write a ‘history so far’ book on behalf of Gelding Street Press for the enjoyment of fellow tragics and casual fans alike.

ORIGINS OF THE SUPERCARS

Each year the newly crowned Supercars champ receives a magnificent Championship trophy. It’s a keepsake that will forever be a reminder of his special achievement; a symbol of superiority for a season of success and hard work. Yet this shiny, handsome piece of modern sculptured metal is not the only trophy he will hold aloft after winning the title. The second is a less grandiose and far more traditional-looking ‘cup’ — the Australian Touring Car Championship (ATCC) trophy. It’s presented by Motorsport Australia, formerly the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS), the governing body overseeing the vast majority of car racing in this country, including elite competitions like Supercars.

The ATCC trophy is a symbol of tradition, a reminder that the origins of the Supercars series date back to 1960. This was when a chap named David McKay drove his Jaguar to victory at a circuit with the unlikely name of Gnoo Blas, at Orange in the New South Wales Central West. This was when the ATCC was held over a single race. From 1969 it was contested over a series of races. It’s an obvious statement, but so much has changed over the six decades the ATCC trophy has been presented. Much of that change is outlined in the 28 ‘year’ chapters in my book, that comprise what we might call the ‘Five-litre V8 Touring Car’ age — what we now know as Supercars.

It’s important to briefly outline how touring car racing in this country evolved over the 33 ATCC seasons held before 1993, when cars conforming to the new V8 formula first contested that title. Not so much in terms of WHO won WHAT and WHEN, but how the rules changed over time regarding the type of cars that were raced. This provides the context for WHY the 5.0-litre formula came into being for 1993 and why it has endured for the best part of three decades. In other words, HOW we got to this point.

In a nutshell… prior to 1960, state-based touring car championships — and sedan car racing generally — were held for cars meant to be in their standard, production form. Slowly, mild modifications were allowed and inevitably some competitors pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable. Rules also varied from state to state, event to event. Things had gotten out of hand until CAMS blew the whistle.

To its National Competition Rules it added a couple of pages standardising the regulations for touring car racing across the states. These additional pages were identified as ‘Appendix J’, a very unsexy label that, in the finest traditions of motor racing in that day, effectively became the name used for the category of racing itself. Clearly there were no marketing gurus in the building at CAMS HQ when this all played out in the late 1950s.

An extension of this rule book development was the decision to instigate an Australian Touring Car Championship for 1960. Thus, motor racing history books record that cars conforming to Appendix J rules contested the first five single-race ATCCs. Jaguars held sway until 1964, when another Britmobile, a Cortina, led home an EH Holden, a Jag and a brace of Minis. Things changed for 1965, when the Improved Production era began at Sandown in Melbourne. This was the Ponycar era and lasted to the end of 1972. Think Ford Mustang, Chevy Nova and Camaro. These American muscle cars were joined on track in the latter Improved Production years by European marques Porsche and Alfa Romeo, and an Aussie car or two, most notably the Norm Beechey-driven Monaros.

Indeed, in 1970 Beechey became the first of many Holden drivers to win the ATCC in his modified HT GTS 350. We must point out at this juncture that Bathurst’s October endurance classic, which was enjoying an explosion in popularity, was held to a vastly different set of rules — the showroom-level Series Production regulations. Series Production cars, which in theory could be driven out of the dealership and straight to the racetrack with only safety equipment added, sometimes joined the Improved Production fields, but never vice versa.

Bathurst’s increased importance saw local car manufacturers Holden, Ford and Chrysler develop hot road cars just so they could race them in the Hardie-Ferodo 500 in a bid for glory and publicity. Something of an arms race ensued, which raised the blood pressure of those in authority, who feared these so-called ‘killer cars’ would fall into the hands of inexperienced young drivers. The situation came to a head after a slow news day in mid 1972, when a Sydney Sunday newspaper published a heavily sensationalised front-page article. The ensuing media storm jolted politicians into pressuring the car companies to end the practice of building Bathurst homologation specials.

Governments threatened to cancel fleet orders from the ‘Big Three’ manufacturers, who quickly fell into line and cancelled plans to launch, respectively, a V8 XU-1 Torana, a Falcon GT-HO Phase IV and a V8 Charger. This episode became known as the ‘Supercar Scare’ and would have massive ramifications for local sedan car racing. CAMS quickly came up with a new set of regulations for 1973 that effectively merged Improved Production and Series Production and ensured that the new category would contest both the early season ATCC and end-of-year endurance races, of which the Bathurst 1000 would be the centrepiece.

This new for 1973 category would become widely known as ‘Group C’ — another bland term from officialdom — and would be in place for 12 racing seasons. This was the period when Peter Brock ran amok at Mount Panorama, winning seven of the 12 Bathurst 1000s contested to Group C rules. He wasn’t quite so dominant in the ATCC, with a greater spread of champions taking home the tinware. Holden fans loved the L34 and A9X Toranas raced during the seventies, ditto the succession of V8 Commodores of the early eighties. Meanwhile, Ford enthusiasts cheered the Falcon hardtops, as they did the boxier XD and XE models that hit the track from 1980. The eighties also saw the introduction of Chev Camaros, Mazda RX7s, Nissan Bluebird Turbos and BMW 635CSis, among others.

It’s fair to say that the Group C period was well loved by fans at the time and, thus, fondly remembered today. That said, there was one group eager to see the end of the domestically developed Group C rules – officialdom. CAMS’s administrators had long been frustrated at the endless squawking that took place between competitors and manufacturers over technical specifications. This extended to endless lobbying of the governing body for rule changes and concessions to individual models of cars. So when an international set of rules, known as Group A, took off in Europe in the early 1980s, CAMS was eager to adopt it locally.

And that’s exactly what happened ahead of the 1985 season. Group C was out and Group A in. The first three years of Group A locally delivered on the promise shown overseas, with a wide spread of winning cars of an equally diverse nature. Six cylinder BMWs and Alfa Romeos battled V8 Mustangs, V12 Jaguars and turbo Volvos and Nissans, while the V8 Holden Commodores were a force at selected tracks, especially Bathurst. After all, variety is the spice of life. But then, in 1988 and 1989, one model of car did virtually all of the winning — the Ford Sierra Turbo, a European-built hatch not sold in Australia.

Group A became known as ‘Formula Sierra’, as teams running other marques bought Sierras in a bid to be competitive. Then, in 1990, Nissan debuted a Sierra beater and the local team run by Fred Gibson did the bulk of the winning. Commodore teams were making up the numbers — with the exception of a memorable Bathurst win in 1990 before the Nissan GT-R was properly developed — and fans who had long supported the General started to lose interest. Spectator attendances fell, as did TV audiences, which made it more difficult for teams to retain sponsors.

Group A was on the wane internationally and fans were calling for the introduction of a new domestic class of racing that would see Holden Commodores and Ford Falcons battle for the race wins. Commodores and Falcons had a stranglehold on the new car sales charts and long-time ATCC and Bathurst telecaster, the Seven Network, was eager for fields to reflect this. CAMS monitored what was going on overseas and wanted to stay in step if possible, so adopted a wait-and-see approach that didn’t sit well with impatient teams, manufacturers, fans, sponsors and Seven. Thus, the V8 rules to be in force from 1993 had a long and tortured gestation period.

By mid 1991, it was apparent that V8s of some description would be racing for the ATCC in 1993, but by October 1991 both Ford and Holden were becoming anxious about the ongoing uncertainty as to the detail. In a joint statement, they threatened to transfer support to other motorsport if the draft rules were not finalised in the near future. The Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS), for its part, was keen to wait to see what the FIA did with its proposed international touring car formulae for either 2.5 or 2.0-litre cars.

Integrally connected with this choice was the question of whether the V8s and the smaller class (whatever it may ultimately be) were intended to be racing at the same speed. When the rules were announced in November 1991, it was thought that the V8s would be running with about 340kW, which meant that they would be a good deal quicker than, for instance, a 2-litre car of British Touring Car Championship specifications. This hardly suited BMW or Nissan, who were both long-time supporters of Australian touring car racing, so during 1992 CAMS started to waiver back towards the idea of a ‘level playing field’ for V8s and the smaller category. This brought howls of protest from Ford and Holden, who made it very clear they could not contemplate the Falcon and Commodore suffering outright defeat by the small cars.

It was an interesting marketing conundrum. On the one hand it was understandable that Holden and Ford might not wish to see their respective large V8s beaten by, say, a four-cylinder Nissan Pulsar. But they could not argue such a case for the BMW — the E30 BMW M3

was a small four-cylinder car but in road trim it was more than a match for any EA Falcon or VN Commodore. By June 1992, by which time it was clear that there was a distinct absence of manufacturers willing to support the smaller classes anyway, the original position was confirmed: it would be 5.0-litre V8s, of a unique Australian brew, and 2-litre BTCC cars, but with the 2.5-litre cars (otherwise known as the BMW M3s) eligible for 1993 only.

Curiously, after so much fuss had been made over the years about ‘Aussie V8s’, the Holdens would be running imported Chevrolet engines, while Ford would also be drawing on US-based engines, all of which would be limited to 7500rpm and a compression ratio of 10:1. But at least the regulations provided a better baseline of mechanical freedoms than those that were available to the Group C cars of the early 1980s. And it was again made clear that CAMS would not hesitate to adjust parts of the regulations if one marque was seen to have an advantage over the other. It was intended to be a parity formula.

Of course this concept had basically been the flavour of the last three years of competition, but few people recognised the substantial change this really represented from the old Falcon versus Torana, Moffat versus Brock days, which were still spoken of with reverence. In those days, a manufacturer could be simply crushed (like Holden in 1977) and would have to fight its own way back (like Holden in 1978). Now, if things looked too grim, it seemed that the losing manufacturer would get a large helping hand from the administrators because each of the two marques was meant to be winning about half the races. It seemed that there would be no casualties in this war.

The weapons of war had their own distinctive look too. The thought processes or discussions by the regulators about the appearance of the cars were never revealed to the public, but the upshot was that the cars had relatively high-mounted rear wings (the dimensions of which were restricted), and full ‘cow-catcher’ front spoilers. John Bowe, for one, said in later years that it may have been better to have opted for the boot-lid spoilers as seen in NASCAR, and many a driver and team owner came to rue the design of the front spoiler, which for many years was very easy to dislodge on kerbs or in collisions with other cars. But the decision as to aerodynamics was apparently final and the battle of the winged wonders was eagerly anticipated. Ironically the chief reason for the over-the-top aero packages had more to do with the past than the future 5.0-litre formula for which they were designed.

When the new cars debuted in the 1992 enduros, they were up against the all-conquering all-wheeldrive Nissan GT-R, which is why they opted for as much downforce as possible. The cars that would become known as V8 Supercars and then Supercars made their debut in the Sandown 500 in September 1992. Three of the new generation cars — two VP Commodores from the Holden Racing Team and the Glenn Seton/ Alan Jones EB Falcon — joined an eclectic field of Group A touring cars and production cars. For the record, HRT’s Tomas Mezera and Brad Jones brought their Commodore home in third outright. Four examples of the new cars made it to Bathurst a few weeks later, with HRT’s Win Percy and Allan Grice coming home in fifth place. Godzilla, the nickname for Nissan’s Group A GT-R, ruled the touring car landscape for a couple of years and had won that dramatic final Bathurst held for the international Group A rules. But it was time for a new group of monsters to take centre stage. ■

(Stay tuned for PART TWO next issue)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Luke West is a life-long motorsport tragic and Australian motoring historian with an eye for colourful characters, quirky content and significant moments. He spent eight years as editor of Australia’s favourite retro motoring magazine, Australian Muscle Car, which followed a stint at Auto Action. He spent several seasons as a V8 Supercars oncourse announcer, including twice anchoring the Bathurst 1000 PA commentary team, and has also dabbled in TV commentary.

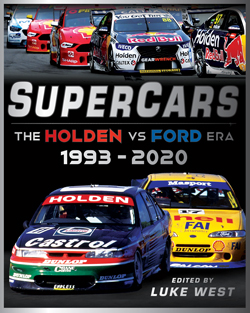

Supercars: The Holden VS Ford Era 1993-2020 (Gelding Street Press $39.99rrp), edited by Luke West is available from July 7 where all good books are sold

For the full article grab the July 2021 issue of MAXIM Australia from newsagents and convenience locations. Subscribe here.